IPhones are ubiquitous, embedded in television shows, movies and many Americans’ hands. On March 21, the Department of Justice filed a lawsuit accusing Apple of acting illegally to secure that monopoly.

University of Virginia School of Law professor Thomas B. Nachbar weighs in on the lawsuit, potential distant implications of the case, and what similar lawsuits in the Information Age can tell us about its anticipated outcome.

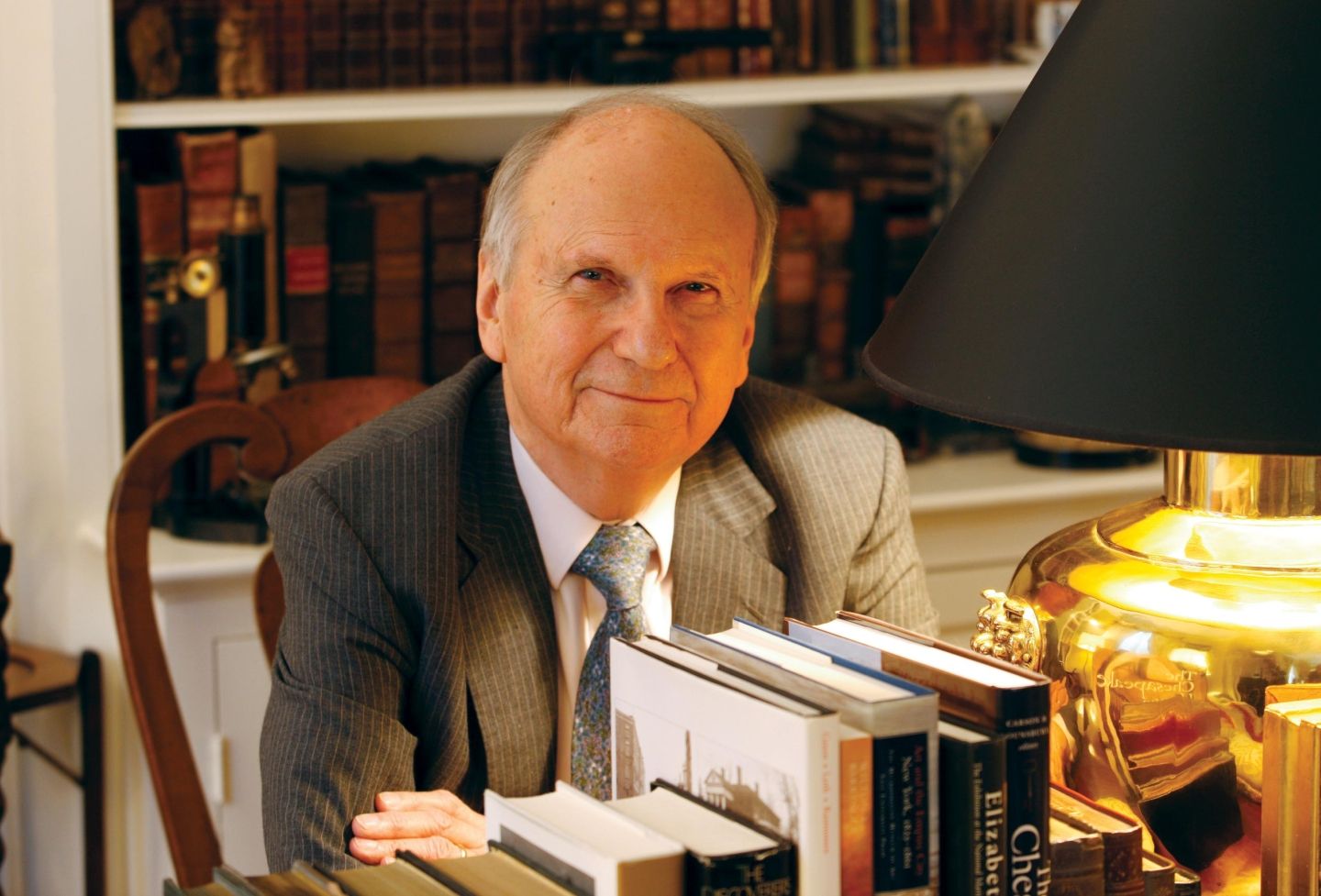

Nachbar is the F. D. G. Ribble Professor of Law and a senior fellow at the UVA Miller Center of Public Affairs.

What is the Justice Department’s legal theory in suing Apple?

DOJ, joined by 15 states and the District of Columbia, sued Apple for violating Section 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act, alleging that Apple is using anticompetitive practices in order to maintain its monopoly in the smartphone market. They’ve also sued Apple for attempting to monopolize the market for smartphones, but that claim is largely derivative of the first.

The basic theory of the lawsuit is that Apple is squelching the development of apps — such as so-called “super apps” that are essentially a gateway to a variety of services or apps — cloud streaming game apps, messaging apps, services (especially financial services, such as digital wallets), and accessories (such as smartwatches) in order to insulate the iPhone from the rise of potential competitors.

There are obvious parallels to a similar lawsuit against Microsoft at the turn of the last century. In a 2001 decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit developed and applied many of the theories that the government has advanced in this lawsuit, including how a company that controls a platform (such as the Microsoft Windows operating system or, as the government alleges, the iPhone itself, which is a platform for other apps and services) might try to prevent the rise of potential competitors to that platform.

Do you have any insights regarding the balance between a company’s ability to control its products and the need to maintain competitive markets?

The Microsoft case itself offers a lot of guidance here. In that case, the court [ruled that] the plaintiff has to show that there is an anticompetitive effect, then the defendant has to provide a procompetitive justification. Then, if the plaintiff can rebut that justification, the court should balance the procompetitive and anticompetitive effects.

Much of the conduct the government is complaining of in this case are things that Apple says it does in order to either protect its users or provide them a distinctive customer experience. Those types of justifications were largely accepted by the court in the Microsoft case.

So, it will likely come down to the facts — how credible Apple’s claims are that its conduct provides a distinct product or improved security. Credibility was a major problem for Microsoft in its case, with some very damning email traffic featuring prominently in the case. The court in Microsoft made it clear that intent is only marginally relevant in cases under Section 2, but statements by executives will feature prominently anyway.

The Department of Justice offers itself a self-congratulatory reference to the Microsoft case in its complaint against Apple, claiming that Apple’s success with the iPhone was due in part to the [settlement in the Microsoft] case.

What are the potential implications for consumers and the tech industry as a result of this lawsuit?

None anytime soon. This case will drag out for a long time. Given that it presents a direct attack on Apple’s “ecosystem” business model, a quick settlement is unlikely.

In many ways, Apple’s degree of control over the iPhone ecosystem is greater than anything Microsoft was accused of. But Apple would say that the control they exercise serves a consumer-oriented business purpose. It’s hard in such a case to identify a compromise position.

There are other cases pending against Apple now, and they recently resolved one brought by a game developer (Epic Games) that is opening up Apple’s in-app payment systems under California law. (Apple prevailed on the antitrust claims brought in that case.) They are also opening up their app distribution, contactless payments, and other browser and interoperability changes in the EU as a result of the EU’s Digital Markets Act. I think we’re likely to see marginal changes from other cases and regulation before we see the kinds of profound changes that this case would require to meet the government’s theory.

Could this lawsuit set a precedent for future antitrust cases against tech companies?

It almost can’t avoid doing so. The complaint specifically alleges that the iPhone is a “platform,” which is an economic phenomenon that applies to almost every major information-driven firm, ranging from Google to Amazon to Meta as well as many non-high-tech products, like credit cards. Even some of the apps Apple is alleged to have harmed (such as “super apps” like WeChat) are themselves platforms. Any decision in this case is likely to serve as precedent for suits against any of those firms, or, for that matter, against any firm that markets both hardware and the software that runs on it, which is really the crux of the issue in this case.

There are many issues with the case, though. In addition to whether Apple’s conduct is anticompetitive, there is the question of Apple’s market power, which is relevant to all of the government’s claims. The DOJ seems to sense that, alleging two distinct but overlapping markets in this case (the market for “performance smartphones” and the market for just “smartphones”), which is a sign that they’re not entirely comfortable with their case on market power. With a case this big, there are any number of ways it could go, not only as to outcome but also its effect on the development of the law.

You mentioned that 15 states and the District of Columbia joined the Department of Justice in this case. What role do state governments play in antitrust actions against corporations like Apple?

Although often overlooked, state governments have broad standing to bring antitrust cases, both under federal antitrust law but also their own state laws. In this case, for instance, there are claims brought under New Jersey and Wisconsin state law. The Microsoft case itself was joined by 19 states and the District of Columbia. Most state antitrust laws track federal antitrust law, so I do not expect a major substantive effect as a result of the state claims, but it’s certainly possible. As I mentioned, Apple recently won on 9 out of 10 claims in its lawsuit with Epic Games, but the one they lost on was under California unfair competition law. Information companies like Apple that operate in so many jurisdictions are affected by a multitude of state and non-U.S. laws, and that will be true even if they win on the federal antitrust claims brought in this case.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.