For a man who has had a hand in more constitutions than all the Founding Fathers put together, it’s a bit ironic that Arthur Ellsworth Dick Howard gleans such special joy from a morning routine he has performed countless times since moving to Charlottesville to teach at the University of Virginia School of Law in 1964.

Howard wakes at 5:30 a.m., retrieves the daily newspaper from the impeccably landscaped driveway near his carriage house and sits down to a bowl of Scottish pinhead oats and half a grapefruit.

As he turned the pages of those newspapers over the years, he would have seen snapshots and clippings of moments from his own remarkable career of more than 60 years.

He would recognize the Rev. Leslie Griffin and his daughter, who convinced the U.S. Supreme Court to order all Virginia public schools to reopen and desegregate — 10 years after Brown v. Board of Education.

He’d spot Clarence Gideon winning the right to counsel for indigent defendants.

Virginia voting Jim Crow and sex discrimination out of its constitution.

Protests in Central and Eastern European town squares, the fall of the Berlin Wall, nascent European democracies and so much more.

Howard has traveled the world and served the world at large — helping to write a dozen democratic constitutions — without ever truly moving out of his native Virginia or leaving the Law School he calls home.

“Many of the most amazing things that have happened to me were not part of my original game plan,” Howard said in his Tidewater accent, sipping tea in a Queen Anne armchair as he reflected. “But from the first day I stepped into the classroom, I knew I was where I ought to be. It hasn’t changed in 60 years.”

His constitutional ideals, his home and his aesthetics reflect the Age of Enlightenment. He trusts in the “fundamental values” and “extraordinary insights” of the men who wrote the U.S. Constitution and believes they intended to leave room for future generations to change and perfect the document’s defects.

“It’s a basic model with some obvious flaws — it was drafted by propertied white men, many of whom were slaveowners. Women and Blacks were not at the table,” Howard said. “But they worked under the Enlightenment idea that there are enduring truths.”

When he formally retires from teaching at the end of the semester, he will be the longest-serving professor in UVA history. He can look back with confidence that he has inspired generations of lawyers and judges who have gone out into the world and — on national and international stages alike — nurtured those democratic ideals.

Born in Richmond’s Ginter Park neighborhood in 1933, Howard was raised by his father — a beloved neighborhood pharmacist — and an aunt who was his father’s younger sister. She gave up her nursing career to move to Richmond to raise Howard and his older brother after their mother died of complications from an ectopic pregnancy when he was just 18 months old.

Ultimately, neither parent would survive long enough to see Howard become one of the University of Richmond’s first Rhodes Scholars, or the top graduate in UVA Law’s class of 1961, or Justice Hugo Black’s two-year Supreme Court clerk. Before any of that could happen, his dad died of a heart attack at age 49.

Howard was 15.

After living at home through college, Howard was commissioned as an Army officer through the ROTC. Eager to see the world outside the parochial confines of Richmond, he marked a preference for any and every station overseas.

Instead, he got stationed at Fort Eustis outside of Williamsburg.

“They put me on the staff and faculty of the transportation school at Fort Eustis for the next two years, writing manuals 50 miles from my hometown,” Howard said with a laugh.

Using savings from his Army pay, Howard went to Paris, bought a car and drove to Istanbul and back with a friend, thus satisfying some of his hunger for travel.

A history and government major in college, Howard chose to pursue law school at UVA because some fellow officers he admired were planning to attend law school there. As a student, he applied for the Oxford Rhodes Scholarship because his law school roommate had applied when he was an undergraduate at Harvard. And Howard first wound up clerking for Justice Hugo L. Black at the Supreme Court, inspired to apply because his best friend from law school was so enthusiastic about clerking.

“Between the time I accepted the job with Justice Black and the date I reported for duty, a seat on the court flipped from conservative to liberal,” Howard said. “After 25 years of so many dissents, suddenly Justice Black’s in the catbird seat, writing many of the big opinions.”

Howard is particularly proud of having worked on Black’s opinions in Gideon v. Wainwright, establishing the right to counsel, and Griffin v. Board of Supervisors, ending Virginia’s “massive resistance” to desegregation.

For a young man who had grown up in the former capital of the Confederacy — “in the shadow of the Lost Cause” and Confederate monuments — helping Black write the order to reopen Prince Edward County’s schools in Griffin felt like “a kind of expiation,” he said.

At Oxford, he studied philosophy, politics and economics under some of the “world’s great minds” and rubbed elbows with future prime ministers and presidents. While overseas, he explored virtually all of the Middle East and much of the Soviet bloc by car. He can even say he spent one night in a Jordanian jail — admittedly, it was for lack of any other place to sleep.

“Being able to do those things transported me — my world couldn’t be the same as it was before,” Howard said. “It gave me a sense of humanity in all its stripes and colors around the world. For a kid who went to a segregated school and had very little contact even with Black people in the same city … my goodness.”

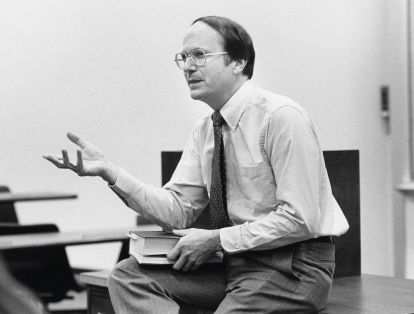

Dean Hardy Cross Dillard ’27 then offered Howard a faculty position at the Law School. In 1964, he began teaching constitutional law, legal philosophy and evidence. Not knowing much about evidence, he relied on friendly student participation and the occasional entertaining “gimmick.”

In one such class, he asked C. Cotesworth Pinckney ’67 — a descendent of a signer of the Declaration of Independence — to read “Julius Caesar” overnight and come back to explain to the class what it has to do with the law of evidence.

Pinckney laid out Caesar’s dead body — that would be Howard’s live body — on the desk, covered him in a shroud and proceeded to recite Mark Antony’s fiery speech.

“For years, I would run into people who’d forgotten everything we talked about in the law of evidence, but remembered that,” Howard chuckled. “If I’d had a gimmick for each day of the class, it would’ve been a brilliant success.”

Howard has treasured his teaching experience and his mentoring relationships with students throughout the years.

“We talk about how special UVA students are, but they really are,” Howard said. “I give lectures at a lot of other universities and law schools; and they don’t have the student body we do. We have students who are bright, they’re engaged, they’re civilized, they’re fun. They’re really human, and they look out for each other.”

Howard acknowledges that he can’t prove this “empirically,” but says the respect and affection that passes between students and faculty “makes this place unique among 200 law schools in the country.”

Students Howard has mentored over the years seem to think just as highly of him.

Katherine Mims Crocker ’12 remembers feeling “nervous” when she first approached Howard to ask him to let her enroll in his already-full Supreme Court seminar. She ended up gaining “a wonderful teacher, but also a model, mentor and friend,” she said.

After the class, Howard asked her to lead a team of research assistants working on what became the landmark article “The Changing Face of the Supreme Court” in the Virginia Law Review. She said the experience working with Howard prepared her for her clerkship with Justice Antonin Scalia.

Howard calls Crocker, now a professor at William & Mary Law School, a “rising star in the legal academy.”

He taught and mentored at least two students who went on to sit on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, including J. Michael Luttig ’81 and J. Harvie Wilkinson III ’72, who served as chief judge from 1996 to 2003. (Howard also taught Wilkinson’s daughter, Porter Wilkinson ’07, nearly 40 years later.)

Calling him an “embodiment of moderation,” Judge Wilkinson said Howard would have made an excellent judge. “But who’s to say his impact as a teacher and scholar hasn’t been just as profound,” Wilkinson said. “Whatever capacity he served in, he was going to make a very positive difference, and there have been generations of Virginia students who have reaped the benefit.”

Wilkinson said he and his daughter were both struck as students by Howard’s accessibility — he was generous with his time and support, and he sets aside erudition in favor of clear communication.

“He would have seminars at his house, and he was never too busy to write a letter or make a call to put in a good word on behalf of a student,” Wilkinson said. “All these same qualities that I had observed in the early 1970s were the qualities that Porter was observing in 2006 and 2007.”

Luttig, a Republican nominee who has made recent news by criticizing Republicans’ attacks on the 2020 election results, said of Howard, “Among teachers and educators of the Constitution and the Supreme Court, as well as scholars of comparative constitutional law, he has no equal.”

Howard has said he is particularly proud of the “nobility and decency” with which Luttig has acted throughout his career, but particularly during his recent outspokenness on the perceived erosion of democracy.

Luttig credits Howard with inspiring in him and others a deep reverence for the Constitution and the rule of law.

“He has lived every day of his sparkling life since joining the faculty educating his beloved students, Americans and the world on the Constitution and the rule of law,” Luttig said. “Himself inspired by the law and the Constitution, he has in turn inspired generations of law students and lawyers to a life in the law.”

His life as an icon of constitutionalism first took off in 1968, when the members of the Virginia Commission on Constitutional Revision chose Howard to be executive director of the commission while he was still junior faculty at the Law School.

For good reason, Howard calls the experience “life-changing,” and admits to being underprepared for the challenge. He claims, almost certainly apocryphally, that he thought there was a form book for this sort of thing.

“I don’t recall my professors at the Law School talking about state constitutions. Very few people even think about them because we’re so bemused by the federal Constitution,” Howard said. “I didn’t tell them at the time that I hadn’t read the old Virginia Constitution and didn’t know what was in it.”

His quick research of Virginia’s and other states’ constitutions revealed that the answer was “far too much.” Seeing Oklahoma define the flashpoint of kerosene and Louisiana enshrining Huey P. Long’s birthday as a state holiday, Howard decided that Virginia’s new Constitution would be like Virginia’s namesake cigarette — slim.

This part has been written before, but it bears repeating. As The Washington Post put it in 1969, “Howard kept the only minutes of the Commission meetings; was the chief author of the changes the revisers recommended; wrote the commentary in support of the recommendation; was public relations man and after-dinner speaker for the group; and, ultimately, was the man chosen to interpret the changes to the General Assembly.”

The commission sent the legislature a revised constitution that was 17,000 words, just under half the length of the 1902 version it replaced. They stripped out poll taxes and other remnants of the Jim Crow South, and got rid of issues that were better left to statute. They added anti-discrimination provisions and wrote in protections for public education, the environment and elderly homeowners facing property-tax inflation.

Lewis F. Powell Jr., who would later become a Supreme Court justice, served on the Virginia commission and told Wilkinson — who clerked for Powell — about Howard’s performance and work ethic.

“He said the committee would meet one day, and by first thing the next morning, Dick would’ve drafted a summary of the comments and a framework and would’ve framed the argument,” Wilkinson said. “Justice Powell said, ‘I’ve never seen anything like that!’”

Howard was pulling all-nighters to produce those drafts and still teach classes. Later, as counsel to the General Assembly, Howard felt like a “one-armed paperhanger” trying to keep track of different legislative committees in Richmond.

“I had to be everywhere at once, because they were depending on me to explain to them what the commission intended, to help them think about whether they wanted to approve it or change it,” Howard said. “And I had to worry about all the parts working together as a constitution.”

Ultimately, 72% of Virginians voted to approve a somewhat revolutionary new constitution, at a time when six other states failed to ratify their own overhauls.

Wilkinson said Howard’s leadership “helped change the posture of Virginia from one of defiance to one of compliance with federal law.”

“The contribution he made in changing Virginia’s whole outlook just can’t be overstated,” Wilkinson said.

There is a scene in “Hamilton” where Aaron Burr points out that John Jay wrote just five of the 85 Federalist Papers supporting the new U.S. Constitution, James Madison wrote 29 and “Hamilton wrote … THE OTHER 51!”

Wilkinson said he sees Howard’s work in that vein.

“Dick not only played the role of executive director — he not only sold it publicly, he not only helped turn the page from the backward constitution of 1902 — he then set to work authoring multivolume commentaries on the Virginia Constitution,” Wilkinson said. “They are the definitive word on our highest law, and it is not an exaggeration to refer to the commentaries as our Federalist Papers.”

“The role that Hamilton and Madison played for the federal Constitution, Dick Howard played for the Virginia Constitution.”

Ultimately, other countries came calling on Virginia’s modern-day Alexander Hamilton. Howard consulted on the drafting of new constitutions for Brazil, Hong Kong, the Philippines and Hungary even before the Soviet Union loosened its grip on Communist Europe.

“In 1988,” Howard said, “I had a call from the U.S. State Department saying, ‘We have a delegation of Hungarian parliamentarians visiting; can we send them down to Charlottesville and have you do a seminar for them on how to write a constitution?’”

The parliamentarians descended on Charlottesville, led by a colorful spokesman wearing an opera cloak. For Howard, it was an early clue to the region’s cultures, values and historical ties that would dictate nuances in their new constitutions. At the invitation of Hungary’s parliament, he made several visits to Budapest to consult on the transition to democracy.

“I think what was happening in 1988 was that the communist regime knew they were not going to be in power forever, but [thought] if they effected genuine change and adopted a new constitution, maybe they would get credit for it and stay in power,” Howard said.

Ironically, while in Budapest, Howard met a 26-year-old Hungarian graduate student who was openly anti-Russia and clamoring for the Russians to leave. His name was Viktor Orban, and he would go on to become the self-described “illiberal” nationalist prime minister of Hungary two decades later.

Those sorts of cultural observations continued to play out as he worked with Poland, Romania, Albania and what was then Czechoslovakia.

“I thought of Czechoslovakia as one country, but the Slovak leadership treated the constitution-drafting exercise as a negotiation between two sovereigns, as if they were making a treaty,” Howard said.

“Countries in that region are very small, but they’re so different from each other,” he continued. “I worked in Warsaw at the invitation of the Polish legislature,” Howard said. “If you get Chicago politics, then you’ll get Warsaw. The executive and legislative branches were at loggerheads the entire time.”

Mark Brzezinski ’91, who became the U.S. ambassador to Poland in late 2021, cited Howard as one of his primary mentors in law school and for the student note he wrote for the Virginia Law Review on the process of Poland reclaiming its 200-year-old democracy after communism.

Brzezinski’s note, “Constitutional Heritage and Renewal,” was published in 1991, and Howard was advising Poland’s legislature while Brzezinski worked on his paper.

“[Howard] gave me a really good sense of the kinds of constitutional choices that each of these new countries would be grappling with in their post-Soviet existence,” Brzezinski said.

Brzezinski, whose father Zbigniew served as national security adviser under President Jimmy Carter, now watches those tradeoffs play out in the real world from his post in Warsaw. He said Howard gave the former communist countries a “jumpstart” on their democracies.

“It was an important role that he played for a part of the world distant from Virginia, but he drew from his Virginia experience that which is universal and transferrable to conditions elsewhere,” Brzezinski said.

As Howard told The New York Times in 1990, “The Eastern Europeans want[ed] to know what comes after ‘We, the people.’” Others did, as well, and Howard went on to advise on constitutions in Malawi, South Africa and Swaziland.

Among a long, long list of awards and accolades Howard has received over his career, the Union of Czech Lawyers awarded him their Randa Medal in 1996, citing his “promotion of the idea of a civil society in Central Europe.” It was the first time the medal had been awarded to a non-Czech citizen.

In 2007, the Richmond Times-Dispatch and the Library of Virginia included Howard on their list of the “greatest Virginians” of the 20th century. Luttig, however, would go further, giving Howard a place in “the pantheon of the greatest scholars of the Constitution since its ratification in 1788 and the great Virginians among our Founding Fathers — George Washington, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson and George Mason.”

Aptly, UVA awarded Howard its 2013 Thomas Jefferson Award, the highest honor given to faculty members at the University. The award commended Howard “for advancing, through his character, work, and personal example the ideals and objectives for which Jefferson founded the University.”

Despite Howard’s sunny optimism and his front-row seat to the Pax Americana era, he acknowledges his concerns about creeping autocracy and Orban-style “illiberal democracy” here and abroad.

“Orban is an autocrat — checks and balances don’t exist in Hungary at the moment,” Howard said. “I worry about the same thing here, that we’re so polarized in the country at large that the Senate and the House can’t even conduct their own affairs. Would I go to a foreign country and hold that up as an example of how a free people govern themselves?”

He cites partisan gerrymandering and felon disenfranchisement as two pressing threats to democracy.

“I believe that if the political system is as close to fair as you can get — one person, one vote, no partisan gerrymandering, free access to the ballot for as many people as possible — if you achieve those, a lot of good things follow,” Howard said. “Of course, bad things happen, too, but that’s democracy.”

If the system is open and fair, he said, you have to trust the people to do the rest. “So much of that is not happening now, and that troubles me.”

But, he added, “maybe I’ve lived long enough to start seeing the cycles of history, because I’m hoping it’ll turn the corner again, even though it can’t ever be like it was then,” Howard said.

He finds his rays of optimism in the exuberant ideals of his students, and in the opportunity to effect change at the local and state level.

“I just think people in this country are mostly good people. I have worked with and taught so many wonderful people across the spectrum, conservative and liberal, who go on to do wonderful things,” Howard said. “If you despair of the national or international scene, you can find outlets for your civic energies where you are.”

It’s not clear what the stories on the final pages of his career will say, but A. E. Dick Howard still has the confidence to write a constitution from scratch, draft a Supreme Court opinion and advise heads of state. He’s also perfectly happy in his garden or sitting in the quiet confines of his home office, working out ways to restore the Virginia voting rights of felons who have served out their sentences.

As his former student Judge Wilkinson said of Howard’s longevity, people often make a deeper impact from setting roots in one place.

“Dick has established this marvelous bond with Virginia and the Law School and the University of Virginia, like an athlete who has spent their entire career with one team instead of being traded here and there,” Wilkinson said.

It’s not what Howard imagined when he filled out that Army stationing request, hoping to see the world. But, as he puts it, he could hardly have imagined what adventures lay ahead.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.