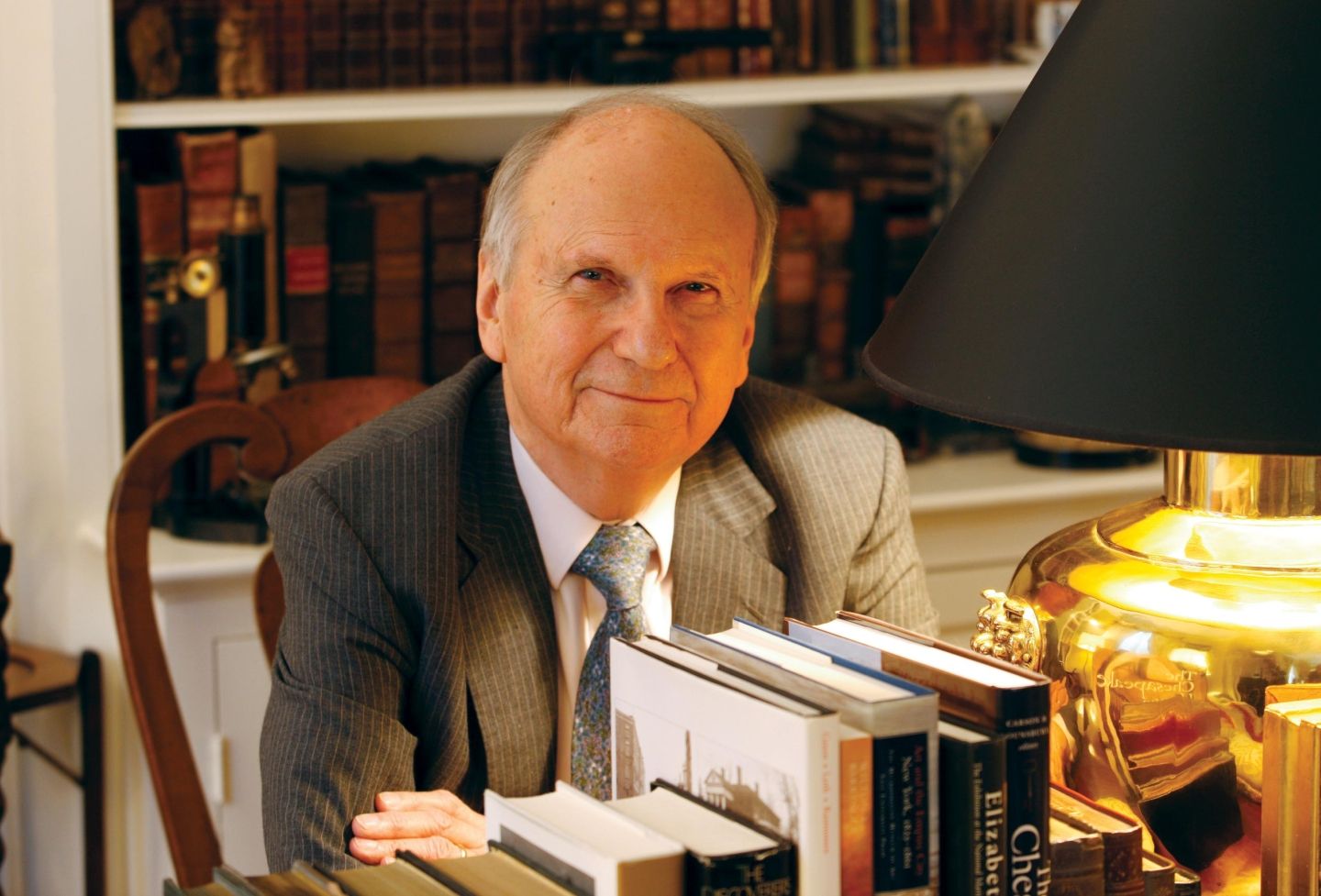

Black Americans sat on juries — and fought to join them as a marker of equal citizenship — much earlier than previous histories have recorded, according to new research by University of Virginia School of Law professor Thomas Frampton.

In his newest article, “The First Black Jurors and the Integration of the American Jury,” forthcoming in the New York University Law Review, Frampton uncovers the story of Andrew Barland, a Mississippian born into slavery who in 1817 became the earliest known Black man to serve in an American jury box — 43 years earlier than previously documented, and 48 years before emancipation.

Piecing together untold stories of pioneers like Barland, Frampton explores original sources to tell a new history about the evolution of jury service.

“We don’t really think of juries today as this site of contestation and struggle,” Frampton said. “But free people of color in the 1870s, 1880s and 1890s were mobilizing around these issues, and we see the jury serving as this place in the fight for equal political rights. In fact, Frederick Douglass frequently spoke about the overarching importance of ‘three boxes’ to the cause of citizenship: ‘the ballot box, the cartridge box and the jury box.’”

Frampton, a former public defender who focuses his research on the intersections of criminal law, racial inequality and social hierarchies, has a keen interest in tracing the history and evolution of jury trials because of the way the institution “continues to both reflect and reproduce racial inequality” in the United States by, for instance, disproportionately striking non-white jurors from the pool.

In an earlier paper, he unearthed the roots of Louisiana and Oregon allowing nonunanimous verdicts for convictions — practices that were struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in Ramos v. Louisiana. The 2020 Ramos decision cited Frampton’s work on how these nonunanimous “Jim Crow juries” were used to negate the effect of empaneling a few Black jurors. And in another forthcoming paper, he analyzes the effects of reform in five states that opted to change their jury-selection rules to make it more difficult to strike Black jurors.

The current paper traces the archival clues that provide the history and context of how Black men came to serve on early juries in antebellum Mississippi, Massachusetts and New York, and in Reconstruction-era Virginia.

By exposing the fact that Black jury service did not begin with the 14th Amendment, Frampton aims to shift at least some of the credit for this aspect of integration away from Congress and the Supreme Court, and give that credit back to the Black citizens who deliberately organized and fought for this particular recognition. His history also seeks to give content and meaning to the rights of citizenship that were ostensibly guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.

“These very fundamental debates over the meaning of equality were percolating for decades [before the Civil War],” Frampton said. “It’s insufficient to look to just the Radical Republicans in Congress or the opinions of the Supreme Court during Reconstruction.”

In dusty archives around the country, Frampton chased clues to find ever-earlier incidents of Black men either serving on juries or agitating for the right to do so.

In Natchez, Mississippi, he stumbled across Barland’s 1824 petition to be afforded the rights of white citizens — including the right to serve on a jury — while looking through a folder of freed persons’ petitions for voluntary enslavement. (Free people of color sometimes petitioned to be enslaved or re-enslaved in order to be able to live with their family members, Frampton said.)

“These were some of the most cursed documents I’ve ever held in my hands — and his was miscategorized — but in that petition, he mentions that among the rights that he had recently been deprived of was his right to serve as a juror as he said he had done in the past,” Frampton said. “As someone who’s interested in 19th-century juries, that was an alarm-bell kind of moment because nobody had known there were Black jurors serving in the 1810s and 1820s. But evidently there were.”

Barland appears to have served regularly on juries but his qualification to do so was called into question when a white man sued him in 1824 — the underlying claim being lost to history — and the plaintiff objected to Barland taking the stand as a witness “on account of his blood.” That, Frampton concluded, seemed to have triggered new scrutiny as to whether he met the citizenship requirement for jurors.

Although Barland is the protagonist in this story of a former slave seizing the rights of citizenship, Frampton noted that Barland’s story is more complex than that. His citizenship claim is based on the wealth and slaves he inherited from the white father who emancipated him. Frampton also shows how Barland’s rights were further eroded as Mississippi’s economic and racial castes hardened.

In the Buffalo History Museum, Frampton found evidence that Abner Francis, a wealthy Black merchant and civic leader, was called upon in 1843 to sit as a juror in several cases involving economic crimes. New York at the time had a property requirement for Black jurors and voters.

“You suddenly see why it might make sense for a white prosecutor to want to have somebody like Francis serving as a juror on cases involving, for instance, passing counterfeit bills to local merchants,” Frampton said.

Searching for news surrounding the trials, Frampton found that Francis had been heavily involved in organizing two conventions that met in Buffalo immediately preceding his jury service. The conventions supported political activism around race, rights and equality — including the right to serve on juries — which Frampton views as another reason why a prosecutor would seat a prominent Black citizen like Francis at that time.

In the days that followed the trials, news reports of Francis’s jury service were reprinted in Rochester, New York City, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. The news then spread to Kentucky and Mississippi the following week and eventually articles appeared in periodicals from New England to the Deep South and as far west as Indiana and the Wisconsin territory.

“It is a testament to the importance of jury service — and the anxiety provoked among many white Americans by the specter of Black jurors — that the events in Buffalo’s Recorder’s Court quickly became national news,” Frampton writes.

His research also took him to Boston and Richmond, the latter being the jurisdiction where Jefferson Davis, former president of the Confederacy, was indicted for treason by a racially mixed grand jury after the Civil War. The record Frampton found was replete with evidence of Davis and his lawyers’ “disgust and panic” at the prospect of facing at trial a jury that included Black citizens. (Davis was never tried and was ultimately pardoned by President Andrew Johnson.)

Frampton said he would be disappointed if the paper and Barland’s story are seen as simply a new “Black first” to celebrate.

“I wanted to tell the story of these extraordinary and interesting individuals, but I wanted to put those narratives in a broader context for thinking about social movements,” Frampton said. “Their stories are interesting for shedding light on what the jury means to different people at different times.”

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.