When Virginia inmate Arsean Lamone Hicks learned of suppressed evidence that could potentially exonerate him of a murder conviction, he was eager to bring the information to light. But under state law, the statute of limitations for doing so had run out. Hicks challenged the law, and the Supreme Court of Virginia agreed to hear his appeal.

Now, thanks to the efforts of the Innocence Project at the University of Virginia School of Law and a group of alumni, state courts must consider illegally suppressed, exculpatory evidence, no matter when it is uncovered.

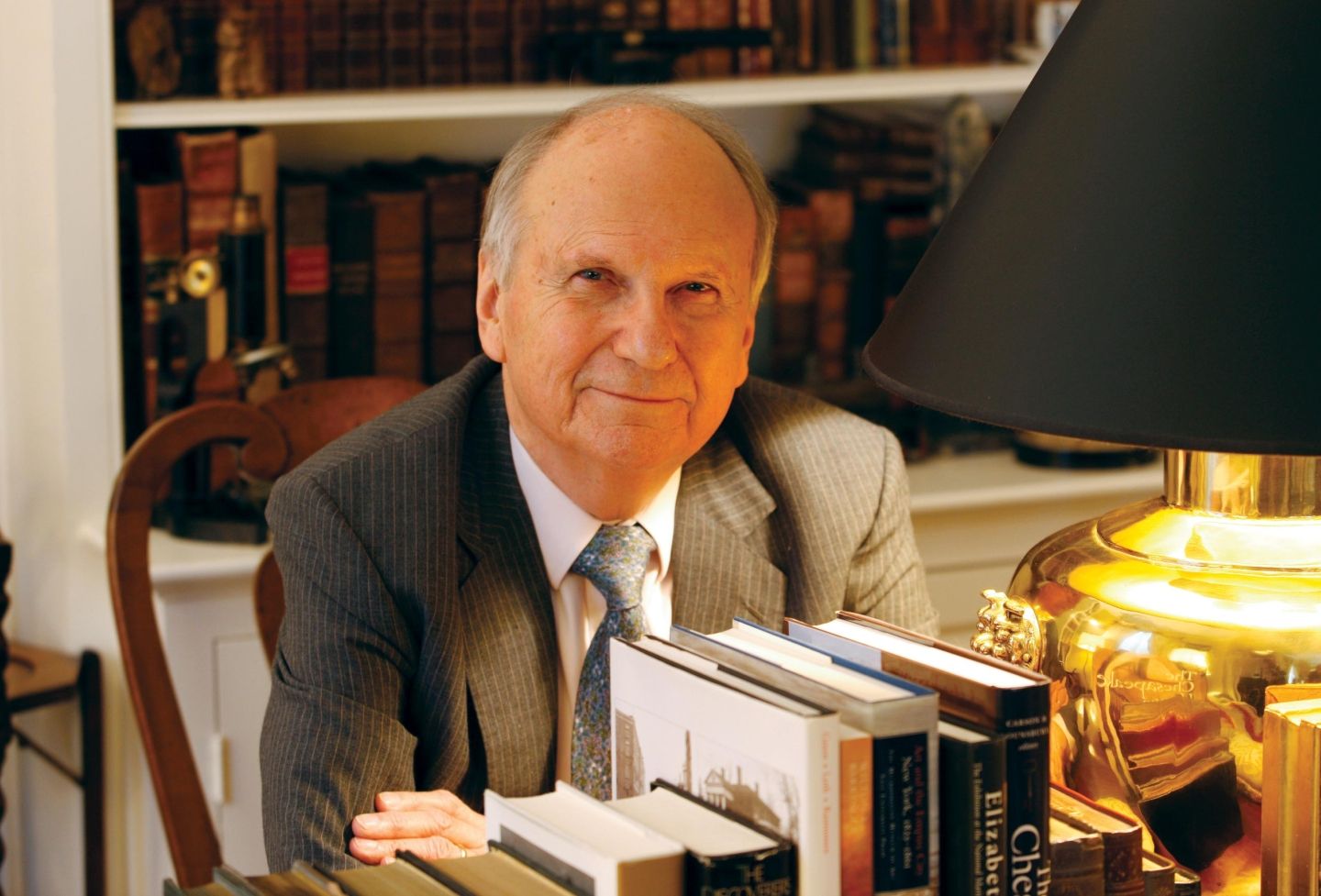

"Not only does the ruling provide for a doorway that didn't exist before, the existence of that doorway makes federal habeas relief more accessible for Virginia inmates," said James Neale, a partner at the McGuireWoods law firm in Charlottesville and a 1998 graduate of the Law School.

The clinic helped Neale and his McGuireWoods colleagues, including several other alumni, prepare the arguments. Students participating in the yearlong clinic investigate and sometimes help litigate cases that could lead to exoneration.

Neale represented Hicks before the court in January, arguing that prosecutors had access to the evidence but didn't present it, in violation of Brady v. Maryland. The U.S. Supreme Court held in Bradythat withholding exculpatory evidence from criminal defendants violated the due process clause of the 14th Amendment.

Hicks was convicted in 2001 of first-degree murder and other charges, for which he received a 150-year sentence, after the 1999 masked armed robbery of a Norfolk diner that led to the death of an off-duty Navy police officer. Hicks later learned that one of his alleged confederates in the robbery recorded a statement about clothing worn by the shooter that, if true, would be exculpatory.

"If he can't put forward this exculpatory evidence because they hid it from him, then essentially that is a suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, because he has live evidence and there is no vehicle for him," said Deirdre Enright, director of investigations for the UVA Law Innocence Project.

In its February opinion, the court held that inmates like Hicks must be able to raise their claims. Senior Supreme Court Justice Elizabeth B. Lacy, writing for the court, said that that the statute of limitations for habeas claims must be tolled while such evidence is suppressed. To "toll" suspends existing statutes of limitation. The court agreed with the clinic's argument that tolling is required by a Virginia law that creates a remedy against obstructions that prevent legal actions from being filed.

In preparing for the Supreme Court appearance, students conducted an extensive review of information, including reading through hundreds of pages of Hicks' court records and transcripts. Hannah Thibideau, a 2015 graduate of the Law School, also surveyed the other states to determine whether they had exceptions to their habeas statutes of limitations similar to one the clinic team was pursuing.

Lainie Singerman, a rising third-year law student, credited their client's interest and involvement in the case as a major reason why his attempt at post-conviction relief has progressed as far as it has. Hicks filed his own petition with the Norfolk Circuit Court on the suppressed evidence, and only when the case reached the Supreme Court did he reach out to UVA for help.

"Arsean is such an amazing client," Singerman said. "He keeps up with all our legal arguments and reads all the cases we read. He's able to discuss it on such an unexpectedly high level. You would think he was in law school."

Alex Cohen, another 2015 graduate, said the experience of working on the case taught him it was critical to hear the client's input.

"I think we learned the value of listening to your client, how important their interest in their case is, and how it can help you figure out the possible route to their objective," he said.

The students said Hicks' case could take years to resolve, but that they intend to stay active and involved with its progress even after they graduate.

Katherine Mims Crocker, a McGuireWoods associate in Richmond and a 2012 graduate of the Law School, said it has been rewarding for her and fellow associate Brian Schmalzbach, a 2010 alum, to maintain their association with the Law School by doing pro bono work on the case.

"Brian and I are relatively new to the firm, and we were both looking for opportunities to be involved in appellate litigation, to do some pro bono work and to maintain our ties with the UVA community," she said. "We enjoyed our time at the Law School, and this gave us the opportunity to do all three at once."

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.