In a Richmond-area juvenile court earlier this month, 17-year-old William (his name has been changed to protect his identity) waited to hear whether a judge would release him early from his five-year sentence for home invasion and armed robbery.

As the judge spoke from the bench about William's case, she praised his efforts to improve himself. While imprisoned, William obtained his GED certificate, received good grades in class, held a job in the facility's cafeteria, was president of his unit and acted as a role model for younger prisoners. He wrote a letter to the judge in which he called his incarceration a "blessing," as it forced him to make changes in his life.

"It kind of became clear that she was going to decide to release him, but she hadn't actually said it yet," recalled Christine Ryu, a student in the University of Virginia School of Law's Child Advocacy Clinic who helped William file for an early release. "She released him and, once it sunk in, he was pretty happy. It's a little overwhelming to get your life back."

William was one of many young clients represented this year by the Child Advocacy Clinic, which provides free legal representation to low-income children across Virginia who are facing problems with the education, foster care and juvenile justice systems.

Ryu and clinic classmate Kelly Quinn collected evidence, conducted interviews, submitted records requests and drafted extensive legal filings to show how their client had become a model prisoner in a juvenile correctional facility over the past two years and how he fought to turn his life around. William's turnaround in prison helped the students make their case, the students said.

"He hadn't been sitting there feeling sorry for himself for two years," Ryu said. "All the staff at the correctional center recognized this and were very complimentary toward him in their interviews with us. We subpoenaed his unit manager — a corrections officer — to come to his hearing and she was in tears. She'd seen him grow and change over these two years, so she was both very happy and sad to see him leave."

After the judge released him, "he said, 'Thank you,'" Quinn said, "and that he was going to go home and have a big dinner with his family."

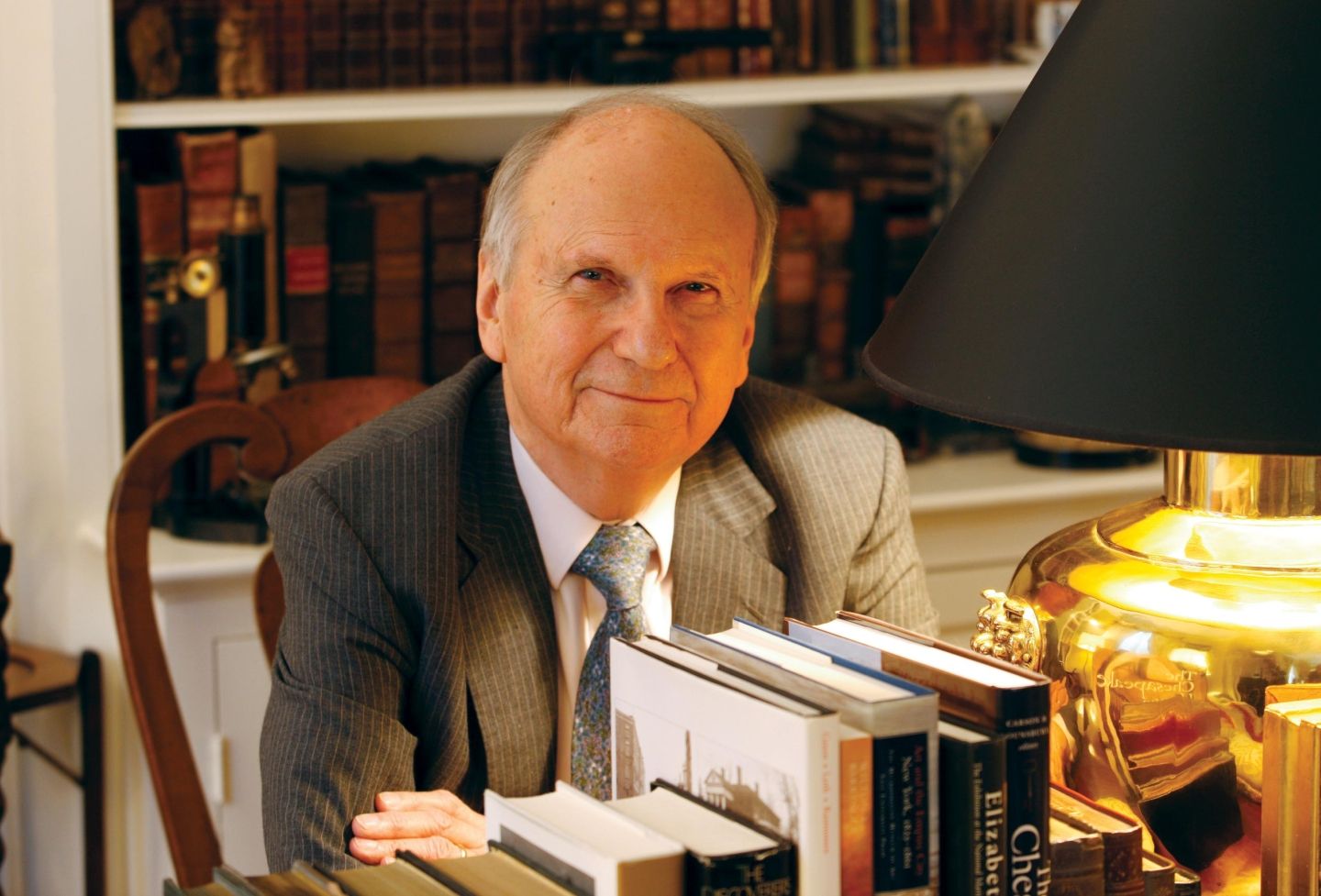

Ryu and Quinn's work was supervised by University of Virginia law professor Andrew Block, director of the clinic. Ryu, in her maiden court appearance, handled the hearing while Block watched.

"It was terrifying," Ryu said. "Going in, I was extremely nervous, not necessarily about having to speak in court but about what the outcome might be. The feeling afterwards was amazing. He got to go home."

Juveniles who are convicted of criminal offenses and sentenced as serious juvenile offenders in Virginia are generally eligible for a hearing on the second anniversary of their sentence, and once every year thereafter, allowing the court to review their progress and determine if they should still be confined until the age of 21.

Quinn said the clinic spent a lot of time preparing for William's review hearing, his first since his sentencing in early 2010.

"We did a lot of writing," Quinn said. "We submitted a brief before his hearing which involved collecting a lot of data. We looked at his record, what he'd been doing over the last couple years. And he'd been doing a great job."

By working with clients like William, the law students learn to put together a case and present it in court, Block said.

"They do all the things that lawyers do to put a case together, and often more than most lawyers who handle cases like this, from factual investigation, to writing legal memos, to preparing witnesses for trial, to appearing in court and presenting the case," he said.

Just as importantly, he added, the students get to feel the weight and responsibility of having a young client's life and future in their hands.

"They get to feel the stress and anxiety that accompanies that responsibility, but hopefully also the exhilaration of seeing a court rule in your favor and impact your client's life in such a positive way," he said.

Two other clinic participants, third-year law students Nate Nichols and Amanda Gray, won another victory in January, securing the early release of a Richmond-area teenager, Robert (whose name has been changed to protect his identity), who had been tried as an adult and was serving a sentence for armed robbery.

Robert had served three years of a four-year commitment to the Department of Juvenile Justice and had a suspended 10-year sentence with the Department of Corrections.

"He'd been [incarcerated] for approximately 75 percent of his sentence and during that time he took full advantage of all the services that were offered to him," Gray said. "He graduated from high school and he had great grades, which was a huge turnaround for him. He received all As and Bs, [and] his teachers all said they really enjoyed him. He kept progressing in the way that we all ideally want children to progress in the Department of Juvenile Justice."

With Block's assistance, Gray and Nichols argued Robert's case at a review hearing in October, while Nichols handled a follow-up hearing in January.

"The hearing went amazingly," Nichols said. "The judge was very sympathetic and willing to listen to the case we'd prepared to present to him. We had everything — letters from his counselors and teachers, we had his counselor on the stand. We threw everything we could at the judge. Even though it was dizzying [and] he had a full docket, he was willing to sit and listen to what we had to say. That was really helpful for us, obviously."

While the prosecutor opposed their motion to release the client early, the prosecutor was not combative and did not challenge the law student's evidence or witnesses, Nichols said.

"Even though we thought we had a pretty good shot at getting [our client] out, we tried to keep his expectations low," he said. "He was just excited and nervous to have the opportunity. Of course, I was nervous and excited at the same time and had to try to keep my own expectations in check."

Gray said she was initially unsure of what to expect in representing a young man convicted of a serious criminal offense.

"I'd never really dealt with criminal issues before," she said. "I didn't know how our client would receive me or what our interactions would be like. But when I first met him, he was very kind. He was very serious about getting out, and about improving his life for the future."

Over time, she said, the law students got to know the client and witnessed his efforts to stay out of trouble and improve.

"He was a child. He made a mistake. It was our job to make sure that he'd still be able to have the opportunities available to other teenagers and adults," she said. "He served his time. I wanted to be able to help him live a life that he could have lived if he hadn't done the crime."

Following his release in January, Robert enrolled at J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College in Richmond and, in addition to taking classes, is working at a job.

Nichols said working on the case gave him an opportunity to gain courtroom skills that will come in handy in his future career as a litigator.

"I crafted an opening, I did two directs and I did a closing argument. It was a pretty amazing experience. It's not the sort of experience you get when you're sitting in a classroom with 100 other people," he said. "It gives me a lot of confidence for when I next enter a courtroom."

"Although not all cases work out as well as these," Block said, "it is always exciting to watch these incredibly bright and talented students apply their newfound skills and exercise both creativity and judgment in the representation of their clients."

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.