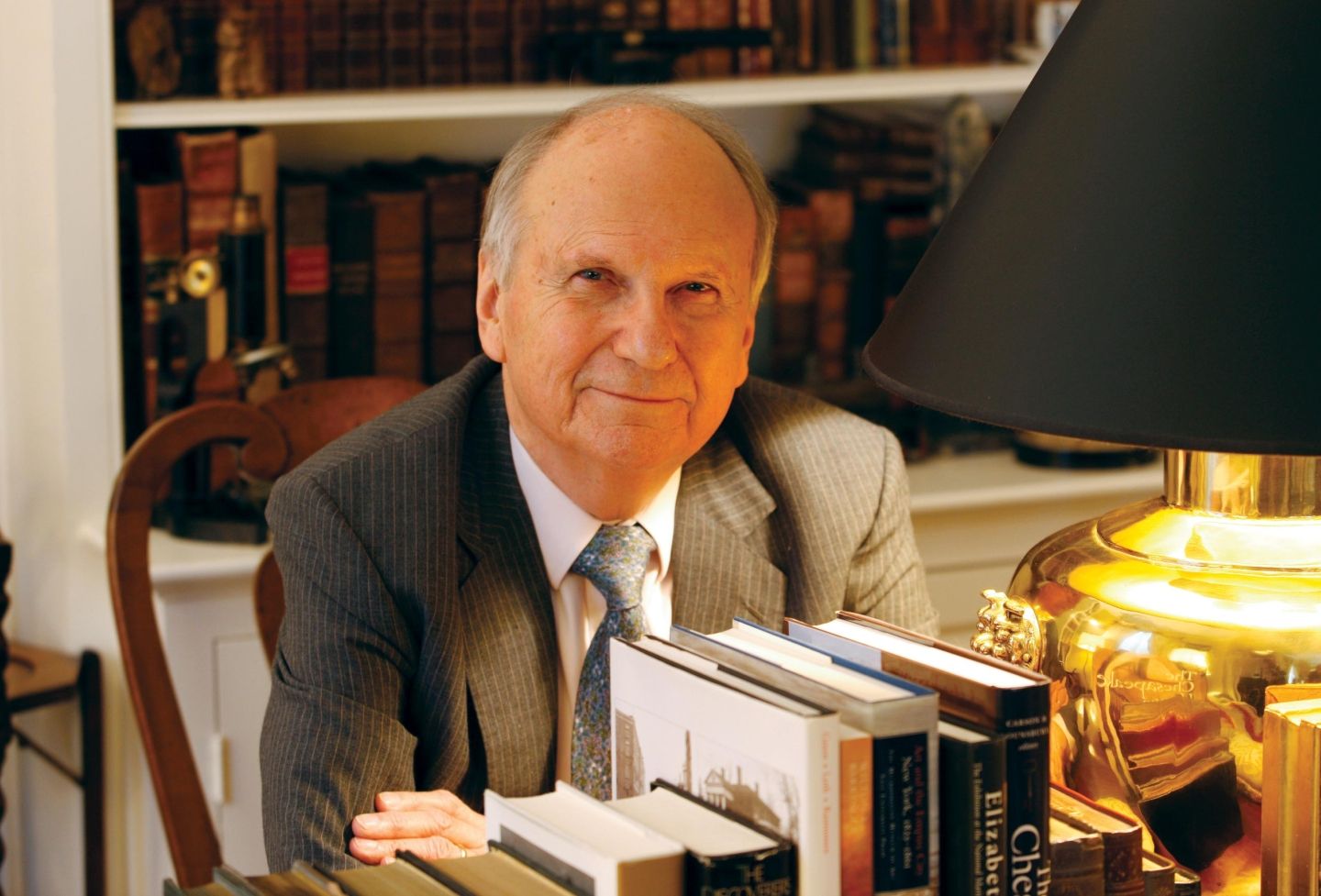

J. Joshua Wheeler '92, a lecturer at the University of Virginia School of Law, was recently named director of the Thomas Jefferson Center for the Protection of Free Expression, a Charlottesville-based nonprofit First Amendment organization.

Wheeler, who previously served as associate director, succeeded the center's founder and longtime leader, Robert M. O'Neil, a former UVA president and Law School professor, who retired in May.

At the Law School, Wheeler is co-director and instructor for the First Amendment Practice Clinic. He is also an adjunct instructor at Piedmont Virginia Community College.

He recently discussed his new position at the Thomas Jefferson Center, his views on the freedom of expression, and his all-time favorite "Jefferson Muzzle," a dubious honor awarded each year by the center for violations of free speech.

How did you become interested in practicing First Amendment law?

My father was a political scientist who taught constitutional law at the undergraduate level for almost 50 years. Family dinner table conversations often turned into lectures on some aspect of constitutional law. He was such a good teacher that, rather than inducing groans or a rolling of the eyes, his dinner lectures" instilled a genuine interest in the Constitution. My specific interest in First Amendment law was due to another excellent teacher, Bob O'Neil, whose course on the subject I took while a student at UVA law. Little did I know then that later I would be lucky enough to work for Bob at the Thomas Jefferson Center.

What is the mission of the Thomas Jefferson Center for the Protection of Free Expression?

The Thomas Jefferson Center is devoted to the defense of free expression in all its forms. We pursue that mission both defensively and offensively. Defensively, we intervene in matters in which someone's speech rights are being threatened. Offensively, we engage in many efforts designed to foster greater awareness and appreciation for the critical role that free speech plays in a democratic society.

When most people think of First Amendment rights, they mainly think of the media. What other types of expression does the center work to protect?

While the center's charge is sharply focused, its mission is broad. We are as concerned with the musician as with the mass media, with the painter as with the publisher, and as much with the sculptor as the editor.

What plans do you have for the future of the Thomas Jefferson Center?

My top priority is to maintain the center's reputation for fairness and nonpartisanship that Bob O'Neil established in his 21 years as director. As far as new or different programs, I am very excited about an annual conference series on timely free speech issues that the center is establishing at the Law School under the direction of John Jeffries. The initial conference will be held on Oct. 29 and will be open to law school students and faculty. I am also looking forward to expanding the work of the First Amendment Practice Clinic, which this coming year we changed from a semester-long program to a full academic year.

Why is it important for the public to understand the need to protect free expression?

I believe the greatest threat to free speech is when too many of us take the right for granted, wrongly assuming our own right of free speech is not threatened by tolerating or even condoning the censorship of others.

What are the most interesting projects you've worked on during your tenure with the Thomas Jefferson Center?

Certainly one of the programming highlights was when we brought Jerry Falwell and Larry Flynt to [the Law School's] Caplin Auditorium to discuss the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case that bears their names. In terms of litigation, the most challenging was Phelps v. Snyder, the case involving Westboro Baptist Church and its protest at the funeral of a U.S. Marine killed in the Iraq War. As was the case with a lot of people, our first reaction at the center to hearing of the protest was that it crossed the line into unprotected expression. When we got beyond the headlines and learned the nuance of the case, however, it became apparent that allowing the church to be held liable in tort could severely chill the exercise of First Amendment rights in other contexts. Although dozens of organizations filed on behalf of the protesters when the case was before the U.S. Supreme Court, the center — through the First Amendment Practice Clinic — filed one of only two amicus briefs supporting the protesters when the case was before the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals. The clinic students also conducted a moot court with the protesters' counsel (a member of the church) just two weeks before she made her oral argument to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The center's Jefferson Muzzle awards "honor" people or organizations that have oppressed free speech. What is your all-time favorite Muzzle Award?

Although far more egregious incidents have earned the dubious distinction of a Muzzle, I have to say my favorite was the one we gave in 2008 to the Scranton, Pa., Police Department for filing criminal charges against a woman for screaming profanities at an overflowing toilet inside her own home.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.