Students Help Clear Backlog of Untested DNA Samples

A group of Law School students is helping state authorities clear a backlog of DNA samples obtained but never tested during criminal investigations in the 1970s and 80s.

Students in the Innocence Project Volunteer Group spent part of the spring semester tracking down people whose DNA was found to be in a state databank decades after their arrests.

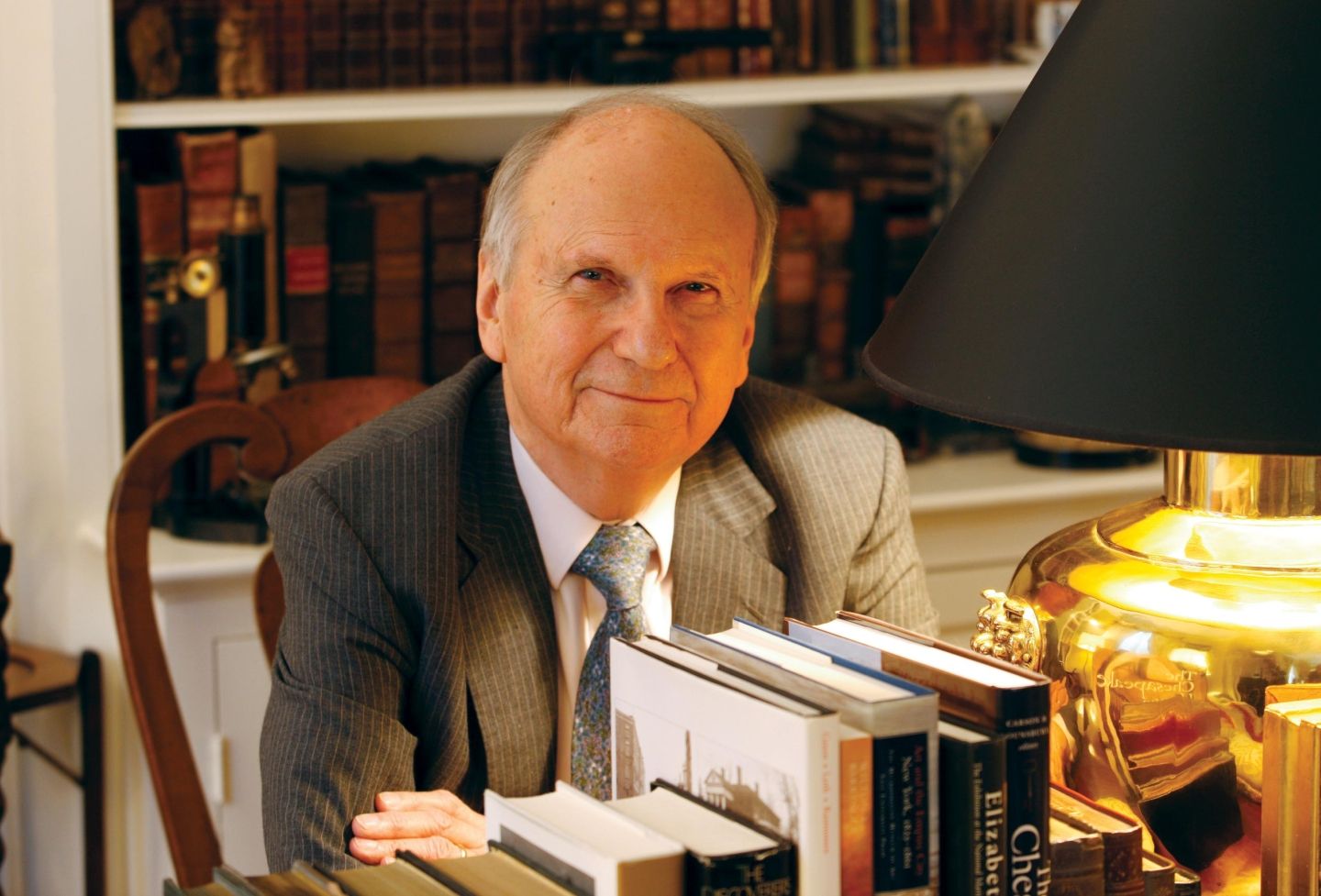

"It started a couple of years ago when a Department of Forensic Science found 1,000-plus samples of DNA" obtained before modern testing methods were available, said Deirdre Enright, director of the Innocence Project Clinic.

In 2008, state legislators directed the Forensic Science Board to make sure those convicted in the cases were notified that DNA evidence exists and is available for testing.

The next year, the state sought help from pro bono attorneys in tracking down and notifying those who provided the samples. In the fall, about 50 UVA Law students organized to assist with the notifications and went through state-provided training.

"We said to the Crime Commission, we can take about 26 cases right off the top," Enright said."And they happened to have 24 cases in the Charlottesville area."

Enright said that in addition to providing experience for students, the project may identify cases in which someone was wrongfully convicted of a crime years ago.

"There are a couple of people [on the list] who are incarcerated, and who could be incarcerated for something erroneous. For some of them, testing the DNA sample might be the logical next step," she said.

Students were assigned to the cases in pairs, and would work first to research the crimes for which the DNA samples were taken. The initial step usually was pulling case files from the Charlottesville or Albemarle County circuit courts, Enright said.

The goal was to learn as much as possible about the original investigation and the resulting sentence. Then students would work to track down a current address, either from court records, inmate locator services or other public databases.

"After that, they actually talk to the person," said third-year student Diana Wielocha, who is head of the Innocence Project Volunteer Group and managed the Law School's DNA notification project.

Students were instructed to notify owners of the DNA samples in person when possible, and to let them know the sample was available for testing if they so choose.

As of April 29, students participating in the project had completed nine notifications, determined that three were out of state, identified addresses for four cases pending identification, and had eight cases remaining.

"Work will be continued on these cases even after students leave for the summer," Wielocha said of the eight remaining cases.

Second-year student Than Cutler encountered the sort of difficulties many students faced when trying to track down those convicted of a crime more than 20 years before.

Cutler and his partner were assigned to notify a man convicted of manslaughter in 1983 that there was an untested DNA sample from his case. The case record was in Charlottesville Circuit Court.

"It was a 10-year sentence, but it's listed as probation on the case file that we pulled," Cutler said.

He and his partner were able to find a last known address from the court file, but it was a dead end. The man they sought had left a substantial court record behind him, however. Cutler and his partner discovered a drug violation from the man's probationary period, as well as a subsequent drug arrest in Oklahoma. The man was incarcerated there from 1996, but the trail ran cold after 2001.

"That's when he exited the Oklahoma system," Cutler said.

Wielocha said that though some students - including herself - ran into problems trying to locate the people from whom the samples were taken, students who participated in the project still learned from the experience.

In addition to performing a civic duty, the students gained real-world experience in case research and honed the type of interpersonal skills needed for client interaction, she said.

"I think that there are a lot of 1Ls involved in the project, and it's been very beneficial for them," she said."As a first-year student, you don't have a lot of involvement with practical cases, so this is very interesting for them. They get to work on projects where they are making their own decisions."

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.