U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who died Friday at age 93, left a lasting impact on American law — and also on the University of Virginia School of Law.

O’Connor, the first woman to serve on the high court, was a William Minor Lile Moot Court competition judge and recipient of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Medal in Law. She was also a friend, mentor and boss at times to UVA Law professors and alumni.

O’Connor served in the Arizona Senate and Arizona Court of Appeals before being nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court by President Ronald Reagan in 1981. She retired in 2006 to care for her ailing husband and was succeeded by Justice Samuel Alito.

Journalist and historian Evan Thomas ’77 published the O’Connor biography “First” in 2019, drawing on exclusive interviews and first-time access to the justice’s archives.

“Justice O’Connor [for] her 25 years was the fifth vote, the decisive vote 330 times,” Thomas told PBS in an interview about the book. “It was Justice O’Connor who kept alive affirmative action for 25 years. It was Justice O’Connor who kept alive abortion rights for 25 years. She was a huge force on freedom of religion. She was the fifth vote in Bush v. Gore. She had enormous power, maybe more power than any American woman has ever had.”

Two UVA Law alumni clerked for O’Connor: Gary L. Francione ’81, during the 1982 term, and Stanley J. Panikowski ’99 in the 2000 term. Today, Francione is a professor at Rutgers Law School, and Panikowski is co-chair of appellate advocacy practice at DLA Piper.

As part of the interview process, Panikowski had lunch with O’Connor and her clerks, chowing down on three bowls of the justice’s homemade spicy bean chili, he told the Virginia Law Weekly in 1999.

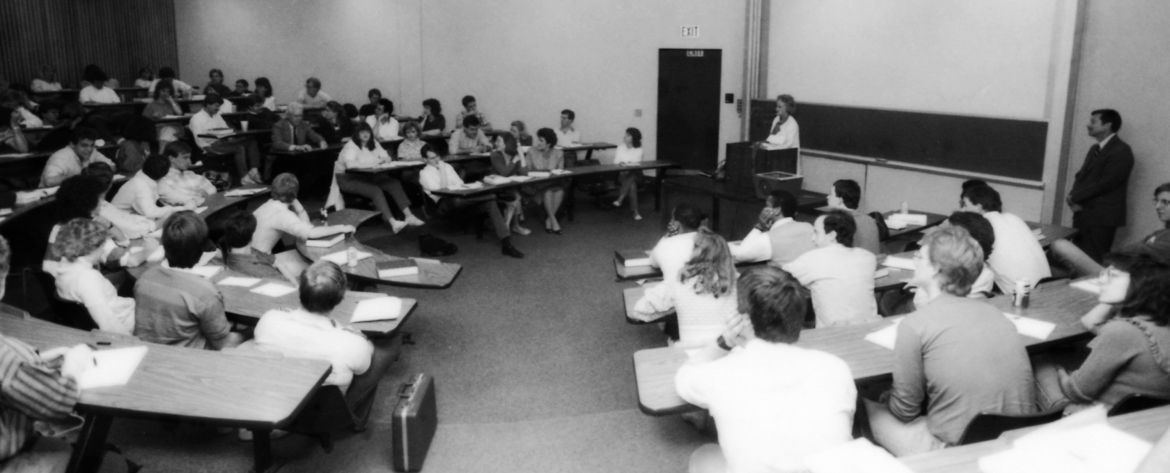

O’Connor visited the Law School a handful of times in the 1980s.

Along with Chief Justice Warren Burger, she came to North Grounds in 1984 as part of a conference with American and British lawyers and judges on administrative law.

In 1985, O’Connor was one of three judges to hear arguments in the William Minor Lile Moot Court Competition finals. D. Ruth Buck ’85, now a UVA Law professor, was a finalist and won the Stephen Pierre Traynor Award for Best Individual Oral Advocate.

Buck said in an interview that mooting in front of a Supreme Court justice was by itself exciting, but presenting arguments in front of the first female justice added another dimension to the experience.

“I would say it was more exciting than stressful,” she said, “figuring that I might not ever argue in front of a Supreme Court justice again.”

Buck recalled that O’Connor’s demeanor during the mooting was more pleasant than confrontational. “I think she definitely set the tone for the bench.”

At a dinner after the event, O’Connor chatted with Buck’s moot partner, Lynne Fleming, about balancing work and child care. O’Connor invited the finalists to the Supreme Court, and they listened to oral arguments in a criminal law case similar to the one Buck had mooted.

Buck reflected on the qualities she saw in the justice: “A person can be incredibly incisive and confident and intelligent, and at the same time be gracious,” she said.

O’Connor was presented in 1987 with the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Medal in Law, which, along with medals in architecture and civil leadership, are UVA’s highest external honors.

In a speech that April, covered by Virginia Law Weekly, she emphasized that the public, along with the legislative and executive branches, also play an important role in upholding the Constitution as the judiciary. For example, she said Americans can petition their lawmakers or run for office themselves.

During her multiday visit, O’Connor and her husband played golf with Dean Richard Merrill and Assistant Dean Elizabeth Lowe, chatted with students and faculty over breakfast, and spoke to a Criminal Procedure class on the workings of the Supreme Court and its agenda.

Professor John Setear clerked for O’Connor for the 1985 term and wrote a paper on his clerkship for the Stanford Law Review after her retirement in 2006. (See former O’Connor clerk Professor Kristen Eichensehr’s remembrance)

He said the justice took a personal interest in her clerks by taking them out on cultural outings, asking about their children (she called them her “grandclerks”) and arranging dates for single clerks. Setear went to the theater on a double date with the O’Connors and white-water rafted with the self-described cowgirl.

As for O’Connor’s work inside the marble walls, Setear said in an interview that her newness to the court at the time of his arrival and her lack of experience in federal cases forced her to take a much more thorough and meticulous approach, a trait that rubbed off on her clerks.

“She was very conscientious,” he said. “She wanted to make sure you got everything right and that you chased down every legal concept or topic or line of cases that might be relevant.”

Setear attributed her swing-vote status to the court becoming more conservative with new appointees over time, but noted that her moderation mirrored her legal management style.

“I also think she was in the middle because she was a careful lawyer,” he said, “and she was a classic sort of common law judge in the sense that she looked at the case before her and the facts before her and she tried to resolve that case, and she was cautious about making sweeping pronouncements and going beyond that case.”

Setear said one key lesson he learned from working for O’Connor as a young lawyer was to listen and respect both sides of an argument, even when disagreeing.

“I always felt that she was listening to both sides,” he said. “Some people thought that she picked her clerks to get a variety of viewpoints in the chamber every year so that she would hear the different viewpoints.”

Although Setear said he thinks O’Connor will be remembered above all else as the first woman on the court, he said the appointment spoke to her intelligence, self-restraint and temperament.

“As I saw her in the middle of the 1980s, Justice O’Connor, as a Justice and as a person of such accomplishment — a woman of such accomplishment — had an aura of perfection and invulnerability about her,” Setear writes in his paper. “But as the years went by, and I heard that Justice O’Connor’s own parents had died, that she had breast cancer, or that she was stepping down from the bench for family reasons, I came to realize that this person of unearthly energy and confidence was nonetheless vulnerable, like all the rest of us, to the passage of time.”

Kristen Eichensehr Remembers Justice O’Connor

UVA Law professor Kristen Eichensehr, a former clerk for Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, is director of the Law School’s National Security Law Center and a senior fellow at UVA’s Miller Center of Public Affairs.

For the self-described “first cowgirl on the Supreme Court,” the term trailblazer is all too apt. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s remarkable career was the product of her inner toughness tempered by her good humor, sharp wit and abiding pragmatism.

Describing the wooden windmills on her family’s beloved Lazy B Ranch, Justice O’Connor explained that they did not have to be beautiful, but they had to work. That same approach might be used to describe her jurisprudence. In her years as the median justice controlling many outcomes in Supreme Court cases, she was guided not by rigid theories but by deep concern for the practical effects of the court’s decisions. The court’s decisions, in other words, had to work for people, society and government.

Justice O’Connor’s concern for people extended also to her clerks. I had the honor of clerking for her in the 2010 term, and throughout the year, she made time to meet visiting family and friends, including ones who joined the early morning “exercise class” she convened in the court’s basketball court for decades. Generations of clerks had their own new generations welcomed into the O’Connor family with gifts of tiny T-shirts emblazoned with “SO’C Grandclerk.”

Justice O’Connor’s unique background and concern about the future led her to advance a new cause in her extremely active retirement: civics education. After leaving the Supreme Court, she spoke to many audiences about how judges should neither be nor be seen as “politicians in robes.” Having been an elected official and an elected state court judge herself, she warned against electing judges because doing so compromises their judicial independence. But her concern for education stretched beyond just the role of the judiciary. In 2009, she founded iCivics to educate children on the fundamentals of democratic government, meeting them where they are with online games that teach about government and laws. iCivics is “now used by up to 9 million students and 145,000 teachers annually in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.”

In her 2018 statement announcing her withdrawal from public life, Justice O’Connor pointed to civics education as key for the future, arguing that it is “vital ... for all citizens to understand our Constitution and unique system of government, and participate actively in their communities.” In words that sum up her own career, she emphasized that “[i]t is through this shared understanding of who we are that we can follow the approaches that have served us best over time — working collaboratively together in communities and in government to solve problems, putting country and the common good above party and self-interest, and holding our key governmental institutions accountable.”

Since Justice O’Connor’s retirement from the court in 2006 and withdrawal from public life in 2018, the divisions on the court, in government and in the country have grown deeper. But she was not one to be easily deterred. She saw the fractures coming and set about to lay the groundwork for bridging them.

Justice O’Connor famously said that she was happy to be the first woman on the Supreme Court, but she didn’t want to be the last. Thanks to her, I and others of her later clerks were born into a world where that particular glass ceiling had already been shattered. But Sandra Day O’Connor didn’t stop there. At every stage in her life, she set a high bar for what one can accomplish with hard work, good will, and a devotion to public service. I miss her tremendously but will forever draw inspiration from her example.

A. E. Dick Howard ’61 Reflects on O’Connor’s Legacy as Justice

A. E. Dick Howard ’61, Warner-Booker Distinguished Professor of International Law at UVA, is one of the nation’s foremost constitutional scholars and Supreme Court observers.

I had known Sandra Day O’Connor ever since she was appointed to the Supreme Court by Ronald Reagan in 1981. Over the years, I have come to have deep respect for Justice O’Connor as exemplifying the best qualities in American public life. She was not in the grip of ideology or partisanship. She approached questions of law with the common-sense qualities she learned on the ranch where she grew up.

During her time on the court, Justice O’Connor was more than simply a “swing vote.” She was in many ways at the court’s center, bridging the divide between justices to left and right. She had a distaste for sweeping categories. She was pragmatic and sensible, concerned about a decision’s practical effects on the parties and on the larger public.

Justice O’Connor had never lacked in self-confidence, a quality she exuded when she met with my seminar students. Yet, at the same time, she showed herself to be open-minded, attuned to the facts at hand, able to find a middle ground that so often eluded others.

Sandra Day O’Connor was the last justice on the Supreme Court to have held elected office. Her world views were honed, for the better, by her service in the Arizona Legislature, where her colleagues quickly elected her as majority leader. There was a time when the Supreme Court’s decisions were shaped by justices who understood the world of politics — for example, Earl Warren had been governor of California and Hugo Black had been a U.S. senator from Alabama. The court’s discussions were quickened because of Justice O’Connor’s legislative experience. We will miss that perspective.

Justice O’Connor left a distinctive mark on the court’s jurisprudence. Together with David Souter and Anthony Kennedy, she crafted the plurality opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey in 1992. That opinion rejected the effort to overrule Roe v. Wade. Instead, the three justices affirmed the constitutionally protected right of a woman to make an intimate choice “central to personal dignity and autonomy.” In so doing, Justice O’Connor helped install the “undue burden” test so central to later abortion litigation.

Another example of Justice O’Connor’s distinctive contribution is the “endorsement” test she advanced in cases arising under the First Amendment’s establishment clause. Thus, when a county in Kentucky posted a copy of the Ten Commandments in the county’s courtroom, Justice O’Connor pointed to the “unmistakable message of endorsement” in the posting — a message incompatible with the First Amendment’s robust defense of religious liberty for peoples of all faiths (or indeed, no faith).

In our polarized age, there is the danger that the partisan divides that beset the country at large will infect — or, at least, be perceived as infecting — the Supreme Court. It is at such times that a voice of moderation, compromise and open-mindedness is all the more needed on the court. Sandra Day O’Connor brought just such a voice to the court. We owe her a vote of thanks for her manifest contributions.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.