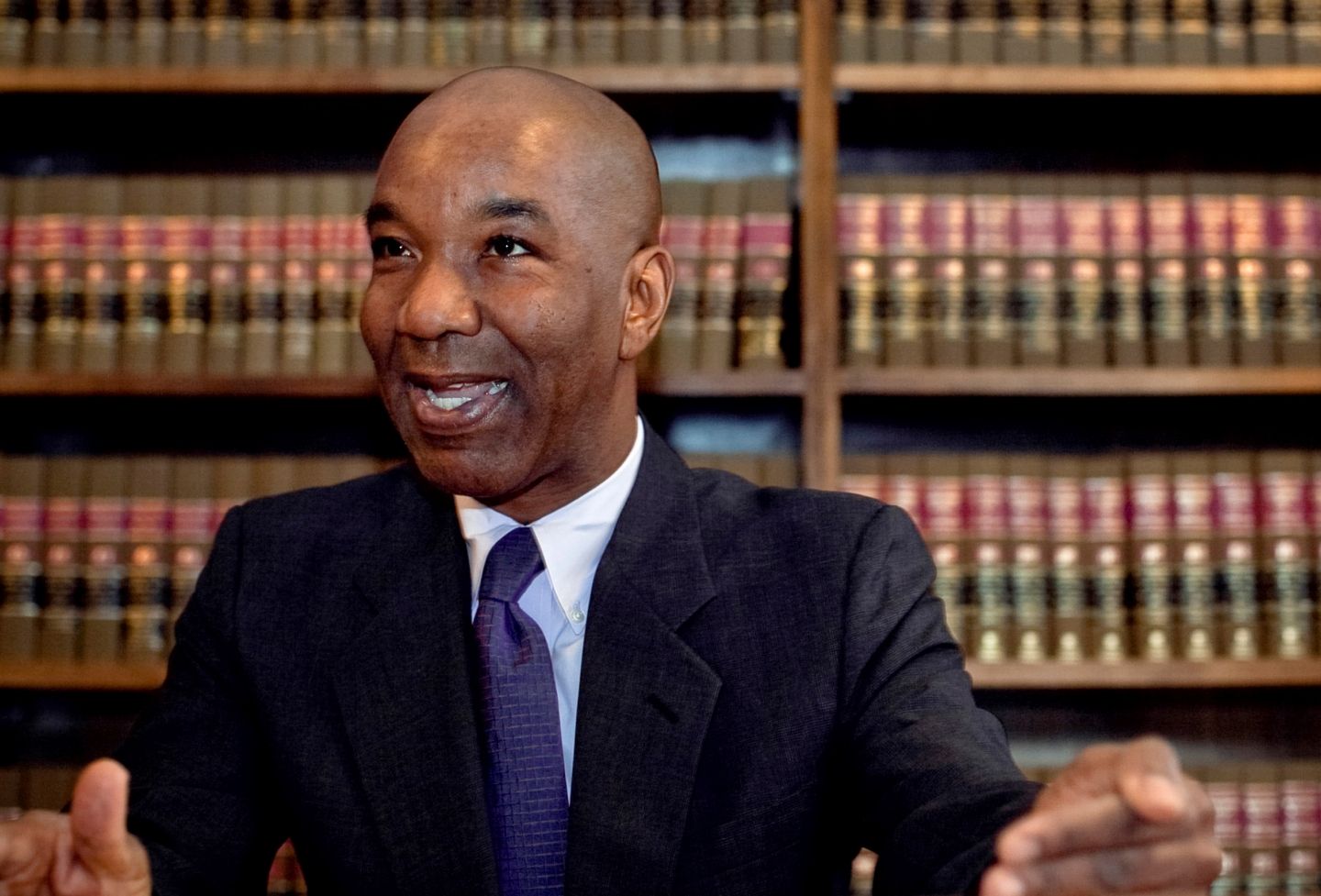

Banks Talks to Law Students about Current Issues in Racial Profiling

Richard Banks, a law professor at Stanford, spoke to Law School students Sept. 21 about the problems that arise from the blurred boundary between discriminatory racial profiling and the more acceptable suspect description reliance in the post Sept. 11 world. Banks' talk was sponsored by the Center for the Study of Race and Law.

According to Banks, racial profiling was first recognized as a problem domestically in the mid 1990s. In terms of the type of people being checked for drugs at motorist stops, there appeared to be “wildly disproportionate stopping of African-Americans,” Banks said. The movement to end racial profiling rose “in response to this abusive practice,” he explained.

According to Banks, racial profiling was first recognized as a problem domestically in the mid 1990s. In terms of the type of people being checked for drugs at motorist stops, there appeared to be “wildly disproportionate stopping of African-Americans,” Banks said. The movement to end racial profiling rose “in response to this abusive practice,” he explained.

Banks gave an example of the negative consequences of racial profiling. In New Jersey, police officers, who were looking to catch criminals with drugs, stopped a van of African-American college students. The students were not in possession of any drugs, but the police shot at them anyway. In response to this sort of event, activists and scholars began criticizing police officers for stopping people “because of stereotypes officers had about who is more likely to be a drug courier,” Banks said.

The movement against racial profiling was very successful, supported by the public, scholars, politicians, and law enforcement officials. Between 1996 and 2000 jurisdictions began requiring data collection and banning racial profiling altogether, Banks said. Both Democrats and Republicans in the 1996 presidential campaign agreed that racial profiling was a bad thing, which caused Banks to become suspicious. “Whenever you see Democrats and Republicans agreeing too quickly about something, there’s something else going on,” Banks joked.

After Sept. 11, the racial profiling debate arose once again, this time in the context of anti-terrorism efforts, Banks said. People debated whether stopping a disproportionate number of Arabs and Muslims in airports was racial profiling, but in Banks’ opinion, this debate was beside the point. Banks concluded that prohibition of racial profiling would do very little to end disproportionate questioning of certain groups of people.

“The term racial profiling has political salience, it has emotional and rhetorical punch, but it doesn’t have any analytical usefulness,” Banks said. Banks explained that there are two categories related to picking out a suspect based on race. Racial profiling means “relying on a stereotype of the criminal propensities” of a certain group, he said. Suspect description occurs when someone has seen the suspect and knows for a fact what race they belong to.

It can be difficult to distinguish between the two categories, Banks explained, especially when it comes to anti-terrorist efforts. “Because the categories blur, many of the practices that might be considered racial profiling might also be characterized as suspect description,” Banks said. For example, if police know that a certain group committed a crime, and they also know that this group only accepts people of a certain race, they will only question members of that race. Some could consider this racial profiling, while others would regard it as part of suspect description, he explained.

Banks pointed out that judging whether a practice is racial profiling or suspect description reliance is an outcome of our reflection on the fairness of the practice. “First we say it’s unfair, then we say it’s profiling,” Banks said. “We don’t say it’s unfair because it’s profiling.”

Banks concluded by reiterating his belief that thinking about whether or not a practice is racial profiling is not helpful. A practice that appears to be racial profiling to some, could be considered suspect description reliance by others. Instead, Banks said, law enforcement officials should consider the seriousness of the crime they are trying to correct, as well as the consequences for individuals and communities of their efforts to deal with the problem.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.