Publisher

Minnesota Law Review

Date

2016

As I will indicate at more length below, I think that three factors explain why Prosser did not focus on what turned out to be the future of products liability. First, throughout his career, Prosser was a no-duty skeptic. He attacked a whole series of such no-duty limitations on the scope of tort liability. He was at least as interested in eliminating these limitations as in the precise scope of the liability that would grow up thereafter. The privity rule was a no-duty barrier to liability. For Prosser, the privity rule was the target; strict liability was the result. The precise scope of strict products liability was therefore secondary to him. Second, most of the appellate cases on products liability that Prosser read and cited involved what we now call manufacturing defects. These cases gave him little reason to anticipate the challenge of defining a design defect that arose later. Third, in considering manufacturers' liability, Prosser may have been thinking mainly of "shoddy" products such as adulterated food or poorly made durable goods whose defectiveness was obvious to him. In this context there would have been no need to attend to possible differences in the causes or nature of this shoddiness.

In short, Prosser had been fighting mainly to remedy the past failings of products liability law by bringing down the citadel of privity, rather than to erect a fully-designed replacement. Because he was recounting the results of that effort in the The Fall, we should understand the article in that context. In the following pages I attempt to do that.

Citation

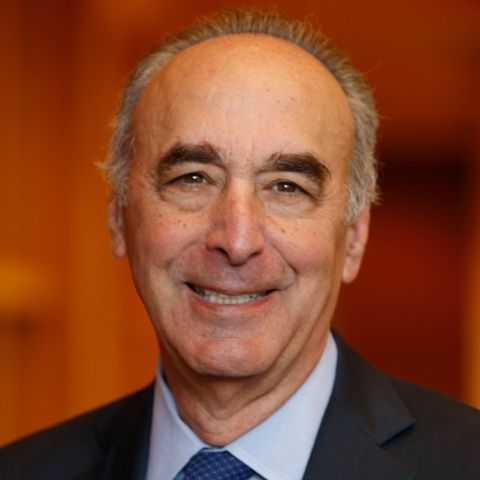

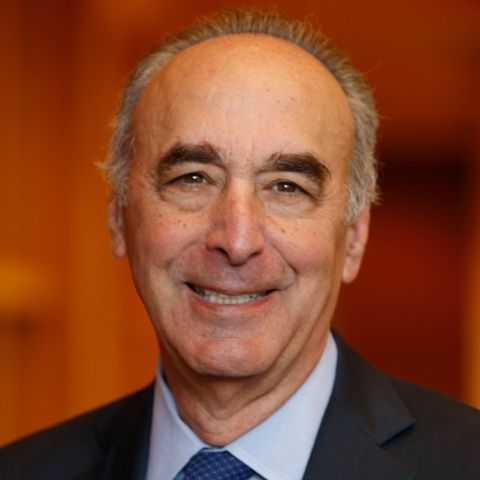

Kenneth S. Abraham, Prosser’s <em>The Fall of the Citadel</em>, 100 Minnesota Law Review, 1823–1844 (2016).