National tax policies have vastly different local consequences, particularly on income inequality, according to a new paper by University of Virginia School of Law professor Andrew Hayashi, “The Federal Architecture of Income Inequality.”

While the national media is focused on the income gap between CEOs and their warehouse workers, that narrative does not begin to tell the whole story, Hayashi said, because those warehouse workers live in different states with different forms of taxation and income redistribution goals. Hayashi argues that we should measure inequality differently to capture local nuance and make federal policy more flexible to address local differences.

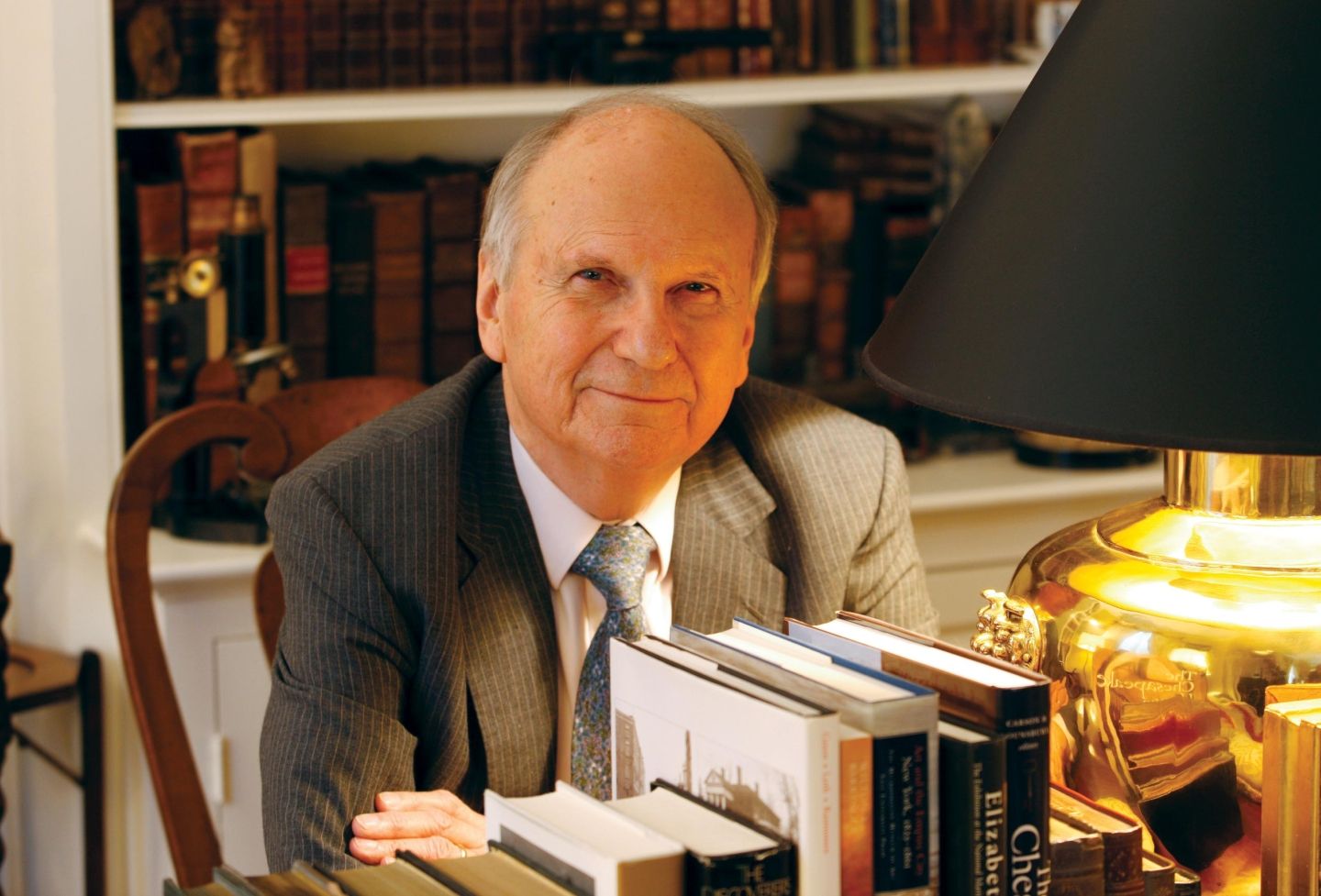

Hayashi — an expert in tax law, tax policy and behavioral law and economics — is the Nancy L. Buc ’69 Research Professor of Democracy and Equity. His research and scholarship explore the unanticipated or hidden effects of tax policy on marginalized groups.

What was the “aha moment” that led you to this research topic?

I’d say it was the personal experience of living in several very different cities in the United States and seeing how the nature of inequality differed in these places. In New York, you have a chasm of inequality created by the high incomes in finance. In Berkeley, you have a big gap between the tech players and everyone else. In Charlottesville, you have an influential academic and professional class. There has also been a lively debate about whether student debt relief is progressive — and therefore reduces inequality — or regressive, and exacerbates it. I think a national policy like that plays out differently in different places, reducing inequality in some places and increasing it in others.

Are you arguing that inequality on a local scale is more relevant?

I do think the problems of local inequality get drowned out sometimes by the national media’s focus on national inequality, but the question of which matters more depends on context and what we are negotiating over. If an economic or social policy is determined at a national level, you’re competing for political influence with people all across the country, so unequal resources and access to power matter at a national level in that case. But if you’re fighting over local zoning policy in Charlottesville, it doesn’t matter how much money [Amazon founder] Jeff Bezos has — he’s not playing in your sandbox. But tax policy can have different national and local effects on, say, housing markets. When we only measure the effects of policy at a national level, we can completely misunderstand the local effects. The truth is that we’re all simultaneously living and competing in multiple different markets or political units — regional housing and labor markets; local, state and national polities; and so on. And it’s not just about whether we “feel” equal in each of those spaces or not — it’s about our ability to access power or influence to change our circumstances or to acquire important goods in those contexts — and that depends on who’s in these spaces with us.

In light of what you’ve learned, what do you propose in your paper?

The paper does three things. First, it documents how much variation in the amount of inequality there is across the country at the local level. Second, it looks at four different national policies to show how widely their local effects differ, in some cases even increasing local inequality while simultaneously reducing national inequality. Third, the paper proposes a new composite measure of income inequality that includes the importance of local considerations. If you don’t acknowledge and measure local inequality, then you will never address it.

Can you give us a quick overview of a couple of those policies you look at?

I analyzed some tax proposals offered by Bernie Sanders, the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, student debt forgiveness and the moratorium on student loan interest. On the last point, for example, I found that student debt forgiveness and the pause on interest repayments reduces income inequality when you measure it at a national level, but that the policies increase income inequality when measured at the local level.

What challenges might arise if we shift the policy focus to address local inequality, and how can these be overcome?

Trying to account for local inequality in national policy makes things more complicated. So, to the extent that states and localities can make decisions about tax policy and wealth redistribution themselves, that’s probably the best solution. But there are also these complicated migration effects as people move to avoid taxes or find a lower cost of living, and those moves are hard to predict.

Do you have an overarching theory of the limits of tax policy to affect equity and human behavior?

There always has to be some modesty about what you hope to accomplish with tax policy, because if you push too hard it can be ineffective and even counterproductive. But I do think there are possibilities for national tax policy as one tool for decreasing local inequality. For example, this paper goes hand in hand with an earlier paper I wrote with Justin Hopkins, “Charitable Giving and Civic Engagement,” which suggested a $500 tax credit for donations to local charities and nonprofits by lower income taxpayers.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.