A law degree from the University of Virginia could result in public service work overseas. It could lead you to a clerkship at the Supreme Court. Or it could set you on the path to litigating against a celebrity billionaire.

David F.E. Tejtel, a 2007 Law School graduate, is a founding partner of a boutique shareholders’ advocacy firm that successfully challenged the largest CEO compensation plan in history. In February, Tejtel and his firm helped Tesla’s shareholders invalidate a $56 billion pay package for Elon Musk, the embattled business celebrity who founded the electric carmaker.

As he reported to the Delaware Court of Chancery for each day of the trial, Tejtel found himself face-to-face with national and international media and celebrity witnesses, such as Tesla board member James Murdoch, son of Rupert, whom he cross-examined. Tejtel, who minored in astronomy as a UVA undergraduate, kept a cool head by focusing on the task immediately before him, blowing off steam at jiu-jitsu and thinking about the infinite.

“Realizing I was involved in something that had the world’s attention was incredibly humbling,” he said. At times, he harkened back to his astronomy studies to keep things in perspective. “No challenge seems quite as big when I remind myself that I’m unfathomably irrelevant on a cosmic scale.”

A Falls Church, Virginia, native, Tejtel had only to visit his older sister at UVA once to know it was where he wanted to spend his college years. He double-majored in English and history, and picked up an unexpected minor in astronomy.

“I just took astronomy classes because I liked them, but my adviser said, ‘You know, if you do an astronomy lab, you’ll have sufficient credits for a minor,’” Tejtel said. “To this day, I’m fascinated by space. I’ll listen to astrophysics lectures and they’re just the most beautiful teleportation device to this impossibly different place.”

While in Charlottesville, he teleported away from stress by working at Wild Wing Cafe above the train station, first as a waiter and eventually as a bartender. He quickly learned that immersing himself in a high-stress activity in his spare time actually helped him recharge and refocus on his primary obligations. It’s a lesson he applies to his current career.

“It required the devotion of every single neuron when I was three people deep at the bar, all screaming for drinks,” Tejtel said. “I’ve got to fill up the ice, I’ve got to replenish the liquor, I’ve got to change the keg, I’ve got to empty the trash — you don’t have room to think about anything else in that moment. So all the stresses of law school vanish for three or four hours.”

During the Tesla trial, he took a similar approach to de-stressing, carving out precious time to drop into Brazilian jiu-jitsu classes in Wilmington, finding that it helped him “clear the palate” and gave him a “meditation effect.”

Brazilian jiu-jitsu is a combat sport based on grappling, ground fighting and forcing an opponent into submission.

“I think of it as a secret weapon to being an effective litigator,” Tejtel said. “Essentially, you and another willing combatant shake hands, bump fists and then try to strangle one another or bring each other’s limbs to the breaking point — then someone taps out and you go again.”

Relative to that “primal” battle, the courtroom seems much more manageable, he said.

Ironically, this cutthroat grappler has valued and nurtured collegial relationships with colleagues and other lawyers since his days on North Grounds. He once missed a class in law school and, within five minutes of its conclusion, three different people had sent him their notes from the day — completely unsolicited.

In his legal practice, Tejtel strives to exercise the same level of collegiality that he was so struck by on Grounds, even with opposing counsel.

“Frankly, I’ve made that sort of my guiding light in my practice of law,” he said. “And so far, it’s paid dividends.”

He said he tries to act with utmost respect toward all, often deploys humor as a de-escalation mechanism and approaches negotiations not as an antagonistic zero-sum game but instead an opportunity to achieve a “win-win.”

When he was clerking for a federal judge in New Bern, North Carolina, the town was small enough that he met nearly everyone within a few weeks, which allowed him to form friendships that he keeps up with even today.

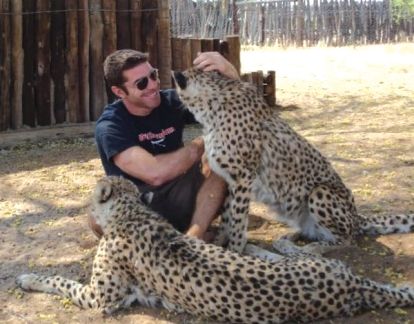

After clerking, he spent three weeks on a delayed post-bar exam trip, volunteering at a wild animal rehabilitation center in Namibia, where he wrangled cheetahs, bottle-fed baby lions and frolicked in trees with adolescent baboons. He also met a fellow volunteer, Ali, with whom he now shares a marriage, three children and two dogs.

“My financial circumstances forced me to choose between a motorcycle or the Africa trip,” Tejtel explained. “For once, I made the right choice.”

Tejtel then spent a few years working at Simpson Thacher & Bartlett in New York, learning the importance of top-quality work and collaborating with “compassionate, conscientious people.”

As grateful as he was for the experience at the firm, he nonetheless found himself struck by the “irrepressible desire to know what lies off the beaten path.”

He thought about his choices as the hobbyist writer he once was, back when he published a short story called “Contractor’s Mix.”

“They asked me to write a blurb about myself and I described myself as ‘an attorney who dreams of being everything else,’” Tejtel said, chuckling. “Looking back, I think that was probably a pretty good encapsulation of how I felt, because I loved the practice of law, but there’s just so much else out there and I was desperate to explore it.”

So he walked off the Big Law partner path and joined his friend, Jeremy Friedman, in co-founding a firm specializing in shareholder advocacy, a specialty Tejtel hadn’t really considered. Friedman, however, was a “powerhouse” in that area, Tejtel said.

He felt a pull to move to the plaintiff’s side because, Tejtel said, “it didn’t sit well with me to be helping Goliath. I felt much more comfortable and fulfilled fighting for David.”

Along with Spencer Oster, the trio launched Friedman Oster & Tejtel in 2014 “on a shoestring and a hope,” with no clients and no office space. They took Greyhound buses to meetings and court appearances, rather than flying, to minimize costs. They did not know if or when they would get paid, or if the firm would survive.

“Plaintiff-side shareholder advocacy sure feels like one of the most difficult practice areas in the world,” Tejtel said. “You’re competing with top-notch opposing counsel with decades of experience and every resource imaginable. You don’t get paid unless you win. If your firm doesn’t win, it dies.”

Musk’s compensation deal had the signs of something that could be problematic under Delaware law. Yet remarkably, and perhaps partially due to Musk’s and Tesla’s track record of being virtually bulletproof in litigation, the only shareholder who stepped forward to prosecute the case was Richard Tornetta, a former thrash-metal drummer, according to reporting in Newsweek.

Pursuing the litigation was an “incredibly difficult road” that required navigating around potential litigation-extinction events and grappling with world-class opposing counsel backed by one of the most well-resourced corporations on the planet. The stakes were high for Tesla’s shareholders, Tejtel’s firm, and for other shareholders and public companies that would be affected by any precedent.

In the end, the shareholders won.

“It’s a good reminder to corporations, directors and shareholders that fundamental rules established by Delaware law for decades apply no matter who you are,” Tejtel said. “And the faithful application of the law, of course, is incredibly good news for those same constituencies, and part of what makes Delaware the gold standard for corporate law.”

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.