A federal appeals court judge, during a talk at the University of Virginia School of Law on Thursday, cast doubt on the idea that the U.S. Supreme Court makes decisions on business cases along ideological lines, or that the court is pro-business at all.

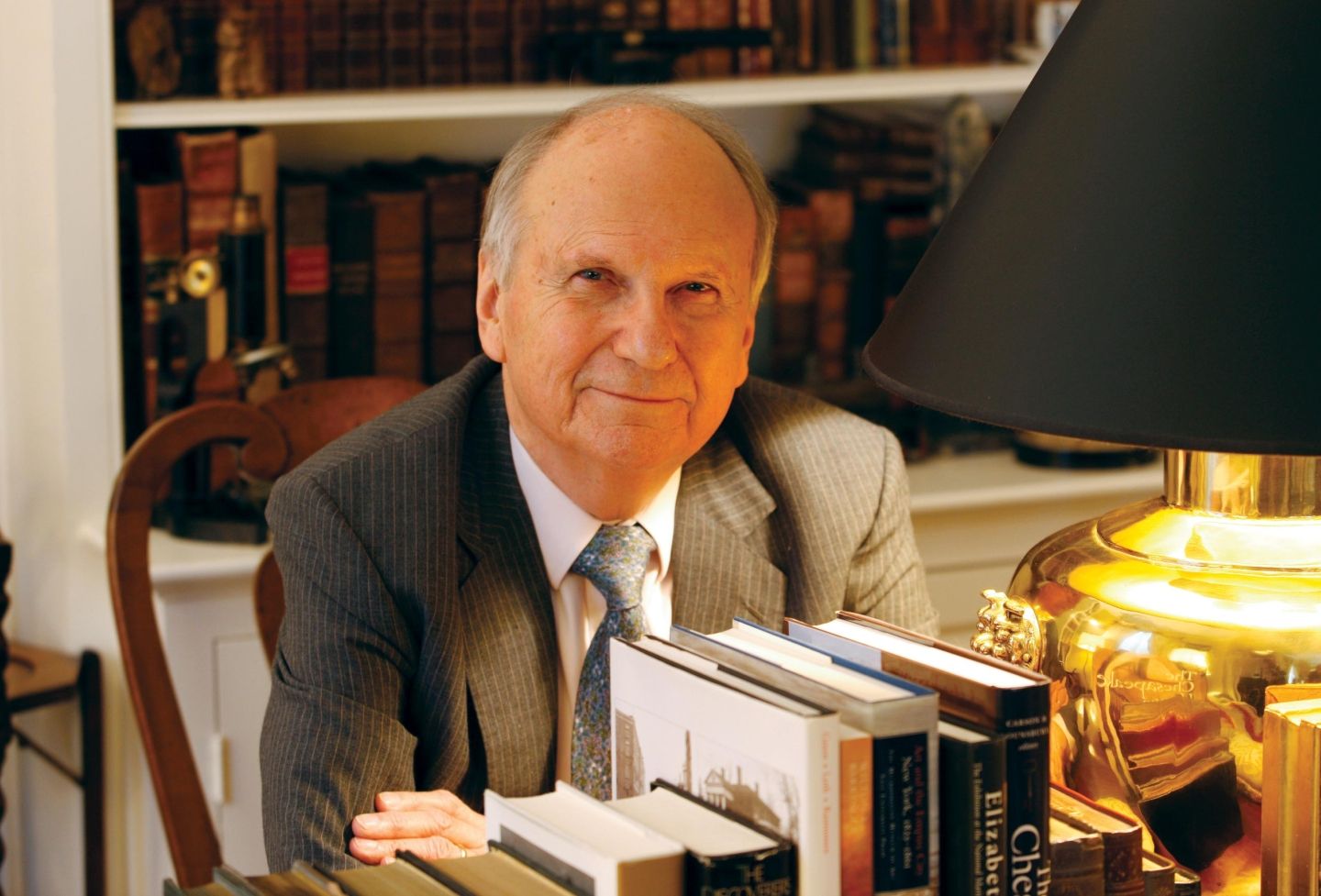

Judge Frank H. Easterbrook of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, this year’s recipient of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Medal in Law, painted the high court as more likely to be politically agnostic than polarized in business cases, contrary to recent high-profile research.

“The world is more complex than left and right,” Easterbrook said.

Easterbrook referenced a recent big-data study that sought to analyze whether justices were increasingly favoring business interests in their rulings. The study crunched decision data between 1946 and 2012. It looked at whether businesses won or lost their cases at the Supreme Court, and whether the results were “liberal” or “conservative.”

“They needed to simplify in order to process larger quantities of data,” Easterbrook said. “They found that the success of business litigants fell during the Warren Court, and has climbed since [1969].”

The study seemed to confirm that the justices became more pro-business over time, and the current court under Chief Justice John Roberts appeared more conservative in such cases than its predecessors.

Easterbrook, one of the most cited appellate judges in the nation as well as a faculty member at the University of Chicago Law School, disputes the study, however.

“Businesses lose major decisions about as much as they win,” he countered.

One reason for the misunderstanding, he said, was how his colleagues’ research was conducted. The methodology for coding such a large data set failed to recognize nuances that might have flagged a case as business-related, or not, he said as one example.

He added that within a set of business cases, many are won on procedural issues that have nothing to do with ideology.

He further stressed that all business cases are not equally important, because they don’t all have the same impact on the business world.

Easterbrook cited his own research published in 1984, which he derived by sampling dockets from each of the three decades prior, as well as his more modern observations. Among his findings:

- About a third of the Supreme Court’s business cases are about procedural, rather than substantive, issues.

- Less than a third of all business cases are about economic issues.

- More than a third can’t be classified on a liberal/conservative basis.

- Business litigants are convincing the Supreme Court to grant review more often because of the justice’s collective interest in such cases, which by default increases businesses’ success rate.

- In many cases, a win for the business may also be a win for the consumer.

- Relatively few cases involved open-ended constitutional questions, and the ones that did resulted in an even split for businesses.

Of the majority of cases, Easterbrook said, “These decisions come out of where the [legislatively] enacted text leads.”

He also cited decisions in which Justice Ruth Ginsburg seemingly wrote a “conservative” opinion, while the late Antonin Scalia, a former UVA Law professor, seemed to have written a “liberal” one.

Regardless, Easterbrook found the notion of Roberts, after becoming chief justice, exercising sway over Scalia’s written opinions — per the perceived trend — to be highly unlikely.

“No one else has accused Justice Scalia of being the weak-minded sort who can be easily manipulated by his colleagues,” Easterbrook said. “Surely he learned better than that when he was a faculty member here.”

While he acknowledged his own research involved greater subjectivity than his colleagues’ study, Easterbrook said it is precisely that subjectivity that provides the needed clarity.

Easterbrook was named to the Seventh Circuit in 1985. He served as its chief judge and a member of the Judicial Conference of the United States from 2006 to 2013.

He is well-known for his writing in the field of corporate law, and for his excellence in legal writing in general. In a brief question-and-answer session that followed the talk, the judge gave law students advice about writing.

The law medal, and its counterparts in architecture and citizen leadership, are UVA’s highest external honors. The actual medals were to be bestowed Friday as part of Founders Day events at the University.

Presented by the University and the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello, the medals recognize exemplars of Jeffersonian ideals in law, architecture and citizen leadership.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.