Richard Balnave first realized he wanted to be a lawyer while working as a teacher. After graduating from the College of William & Mary, Balnave signed up for the Teacher Corps, a precursor to Teach For America, and taught low-income students at a middle school in Schenectady, New York.

One of his students had a reputation for being difficult to deal with, but was finally making steady progress in his education. Yet he ran afoul of the law, and after a swift court session, he was sent to a juvenile facility — his promise potentially wiped away.

"I looked at the effort that was put in to helping kids in school and the results that took a very long time to show progress," Balnave said, "and then I looked at the short amount of time and the major impact on that kid's life that the lawyer and the judge had, and I decided I should be in the field of law, where it was easier to accomplish big things for kids."

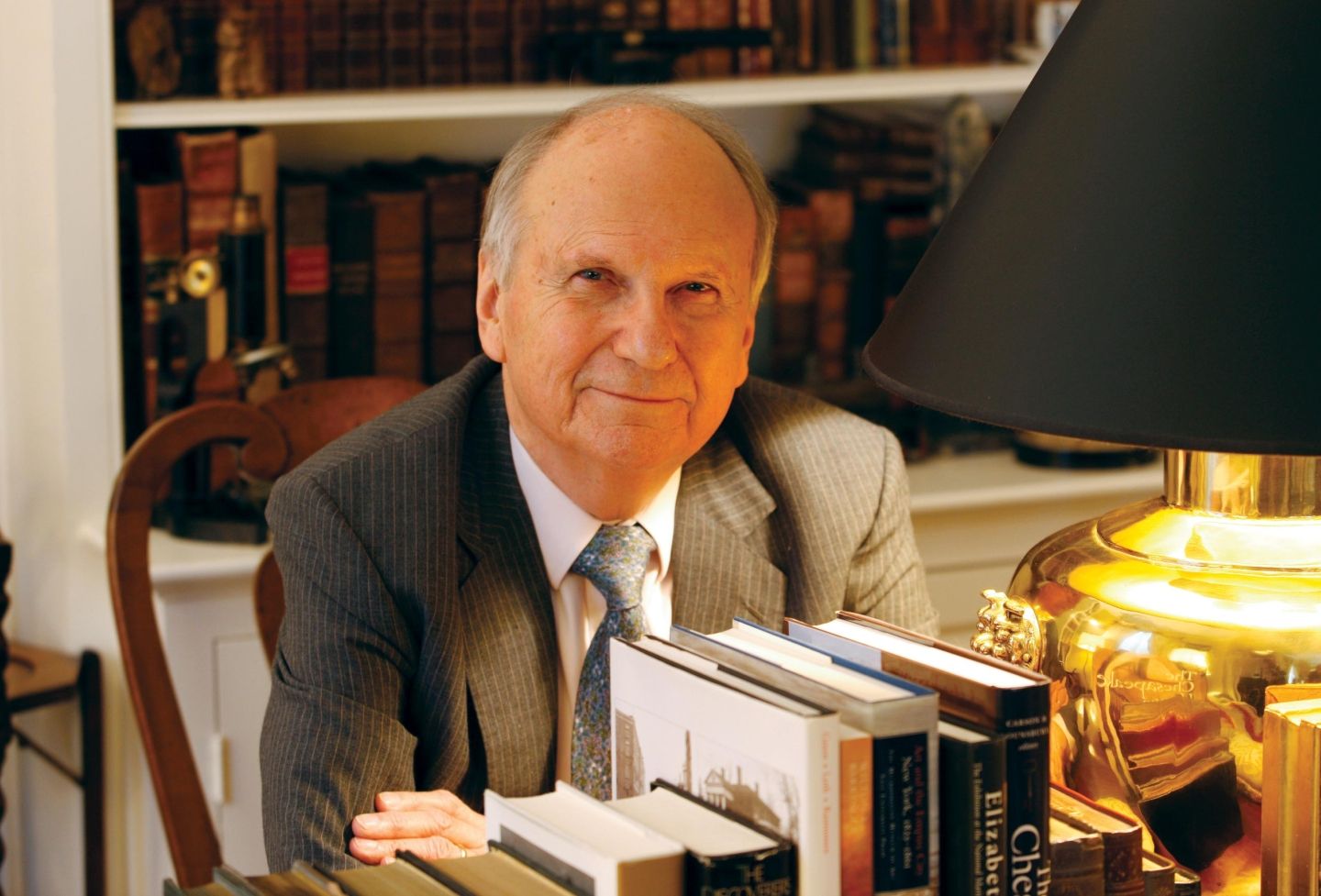

Balnave, who will retire from the Law School at the end of May after teaching a range of clinics in family and children's law, as well as courses in professional responsibility, dedicated his work to improving the lives of young people — including those old enough to go to law school.

Angela Ciolfi '03, litigation director and former legal director of the JustChildren Program at the Legal Aid Justice Center, has known Balnave since she was his student, and later as a colleague.

"The sharpness of his intellect is matched only by the bigness of his heart," Ciolfi said. "You'd be hard-pressed to find a more thoughtful professor, mentor or colleague."

Back to School

Balnave, who is originally from Glen Rock, New Jersey, graduated from Case Western Reserve University Law School in 1977. He and his wife, Linda, moved to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, so he could start his career in family and children's law working for Legal Services of Northeastern Pennsylvania. He spent seven years in the area, half as a legal aid lawyer representing children, practicing family law and human services law, and the other half in private practice as counsel for social service agencies in Luzerne County.

By the time he applied to direct the new UVA Family Law Clinic, funded with national grants by the Legal Services Corporation, Balnave was an experienced attorney.

"The biggest challenge at that time was thinking about what would be good educational goals for the students and what is it they need to learn how to do in order to properly represent clients," he said.

He taught the Family Law Clinic for 16 years, along with various adjunct co-instructors, and represented clients in cases before the juvenile and domestic relations and circuit courts in the Charlottesville, Albemarle and surrounding areas. Over the years, hundreds of students took the clinic.

Balnave adopted creative solutions to teaching problems the clinic posed.

Though legal cases can bring out emotions in clients, disputes about child custody or support are particularly fraught for those involved.

"We would have a number of classes and simulated exercises about interviewing clients and counseling clients, active listening and patience, to let clients feel like they're being heard and [can] tell their whole story," Balnave said.

But most of the challenges the students faced were far more traditional: learning good judgment, thoroughly preparing for court, planning for a trial, and planning again for surprises in case it doesn't go as expected.

"I try to help the students understand how very, very thorough preparation yields good results in court," Balnave said. After the Child Advocacy Clinic was launched in 2000, Balnave created the Family Mediation Clinic, now the Family Alternative Dispute Resolution Clinic, with Assistant Dean for Pro Bono and Public Interest Kimberly Emery '91, in 2009. Shortly after joining the Law School, Dean Richard Merrill asked Balnave to teach a simulated criminal law clinical course based on a course developed at Columbia Law School. For a few years the school tabled the Criminal Defense Clinic and tried this alternative approach. One of the curricular efforts Balnave is proudest of was this "dynamic" simulation course, which he ran for three semesters starting in 1987 with then-trial attorney (now a retired judge) Ted Hogshire '70, who is still a lecturer at the Law School.

The class allowed students to make the same types of judgments that lawyers make — what charges to bring, what defenses might be raised, which possible witnesses to use — while they prepared to try cases involving a conspiracy to deal in stolen explosives and an attempted hijacking. The effort entailed hiring a cast of two dozen actors and actresses, motions hearings before real judges, oral arguments in front of a panel of Law School faculty (including former professors Bill Stuntz '84 and Stephen Saltzburg), and culminating in daylong trials presided over by U.S. District Court Judges James Harry Michael Jr. '42 and James Turk.

"It was very demanding for students," he said. "And it gave the students a sense of how you have to think down the road when you're preparing for trial."

Balnave has also taught Professional Responsibility for decades at the school, and pioneered a special course that was initially suggested by one of his students, Ryan Almstead '06. The course, Professional Responsibility in Public Interest Practice, has been offered since 2007.

Since 2011, Balnave has served as director of clinics for the Law School. Balnave said he was picking up the torch of Professor Kent Sinclair, who performed the same duties for 25 years before him.

"I learned a lot from him because I was on a faculty committee that worked with Kent about developing clinics," he said.

Teaching What Students Need

Balnave said a highlight of his career has been working with the bright students UVA Law attracts.

"It's a joy to work with them and I can feel the energy in the building rising in the month of August as they return," he said.

Yet there are always some students who feel like they're not measuring up to their peers, he said.

"They might feel like they need help with their writing, they can't speak as articulately as some of their colleagues or they're not as quick with their analytic abilities," Balnave

said. "And it took me a while [to understand this] because a practicing lawyer doesn't always have to deal with that."

Balnave met with those students privately to talk about what they needed help with.

"Then we would work together to make a plan for how to address that. And I would alter my assignments in clinical courses to make sure that if the student, for example, wanted more writing opportunities and feedback on writing, then that's the kind of work that they would get. If they feld inadequate about, or overwhelmed by, the prospect of going to court — which is a very normal feeling for any young lawyer — [then I would] spend more time with them so that their anxiety goes down and they feel very, very well prepared."

Balnave recalled when a judge in Nelson County wrote a note during the end of a court hearing at which a student served as counsel.

"I wondered what he was writing," Balnave said. "And when all of the closing statements were made and he made his decision and we were all about to pack up and leave, he stopped us and he pointed to the student and said, 'Please come to the bench.' And he handed her a note, and when she opened it, it had a beautiful compliment about her job. So the judges and other lawyers in town have been wonderful with our students."

A Lawyer for the Community

After having Balnave as a professor and mentor, Ciolfi, the Law School's third Powell Fellow in Legal Services, later worked with him as a co-instructor.

"He is incredibly patient and very thoughtful about how to convey complex concepts in a concrete way," Ciolfi said. "He'll remember what it's like to start with nothing as a student or young attorney — to start at ground zero or step one."

Ciolfi said Balnave has played an important role in the community as a guardian ad litem.

"He's taken some of the most challenging cases for kids who are in foster care," she said.

He was one of the first local lawyers to take SIJ cases — when a young person from another country is abused, neglected or abandoned by one or both parents, they can apply for Special Immigration Juvenile status. When Legal Aid Justice Center's JustChildren Program started to work on SIJ cases over a decade ago, they relied on Balnave's experience.

"Some thorny problem would come up and we would call Rich," she said. He played a significant role in training pro bono attorneys across the state to handle SIJ cases as LAJC started a new statewide project with the Virginia State Bar to increase capacity to provide legal representation to refugee children. The project has handled approximately 150 cases over the past few years.

"We are so lucky to have such a strong relationship with the Law School, and I think Rich has been a huge part of that bond that we have."

Balnave mentored Mario Salas '14 through the Program in Law and Public Service, which involved helping Salas design a paper and supporting him through fellowship applications. (Salas later became the school's 13th Powell Fellow.)

"His door was always open and I always felt like I could talk to him about, really, anything," said Salas, now an attorney with the JustChildren Program. "In the Family Mediation Clinic, we were dealing with some pretty heavy issues in the cases that we were handling — the families all were going through separation and dealing with custody issues. He was so supportive and willing to address those issues with us."

Balnave offered kind words for the Law School faculty and staff, including the clinical faculty and faculty assistant Cindy Derrick. He also praised the local community of practicing lawyers and judges, particularly for supporting young lawyers as they learn.

Balnave said he was grateful to have "one foot in the academy." "Clinical faculty are fortunate relative to lawyers in the private sector because we can choose our cases and we can give them as much time as needed because we're not charging our clients by the hour," he said.

Balnave finished representing his last client from the Child Advocacy Clinic in January.

"I started representing her when she was 7 years old, and she just turned 18," he said. She was initially removed from her home due to child neglect, then both her parents died within a few years of each other. She remained in the foster care system until she aged out, and now "she's doing quite well."

"To see the challenges over and over again that poor people face, and to see some of them respond with tremendous resilience, is really heart-warming," he said.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.