Matt Madden '07 was among a group of University of Virginia School of Law students signed up for a new clinic that had them doing some summer "homework" before the start of the school year — monitoring the federal appeals courts for cases that might attract the attention of the U.S. Supreme Court. Madden saw potential when he happened upon Watson v. United States.

"Watson was an unpublished decision by the Fifth Circuit, a very short opinion in which they applied prior circuit law to Mr. Watson's case, but that circuit law was in disagreement with other circuits," Madden said. "We started looking into whether Mr. Watson's case would provide a vehicle for the Supreme Court to resolve the then-existing circuit split."

The yearlong Supreme Court Litigation Clinic, which officially launched in the fall of 2006, chalked its first win with the case in 2008. The justices issued a 9-0 opinion in favor of Watson.

Each year 12 or more UVA Law students continue to scour appellate court dockets for potential clients. When a client agrees to work with them, the students write their most persuasive briefs and, with a little luck, make a trip to Washington, D.C., to hear their arguments make history.

Ten years after the clinic began, the number of cases the clinic has taken on and successfully argued is the envy of any law firm in the nation.

Of the 12 cases the court has heard, Virginia has won eight and a split decision in a ninth case.

For the 2012 to 2015 terms, the clinic’s record for having cert petitions granted ranks second among all nongovernmental actors, according to a study soon to be published in the Villanova Law Review. That includes law firms.

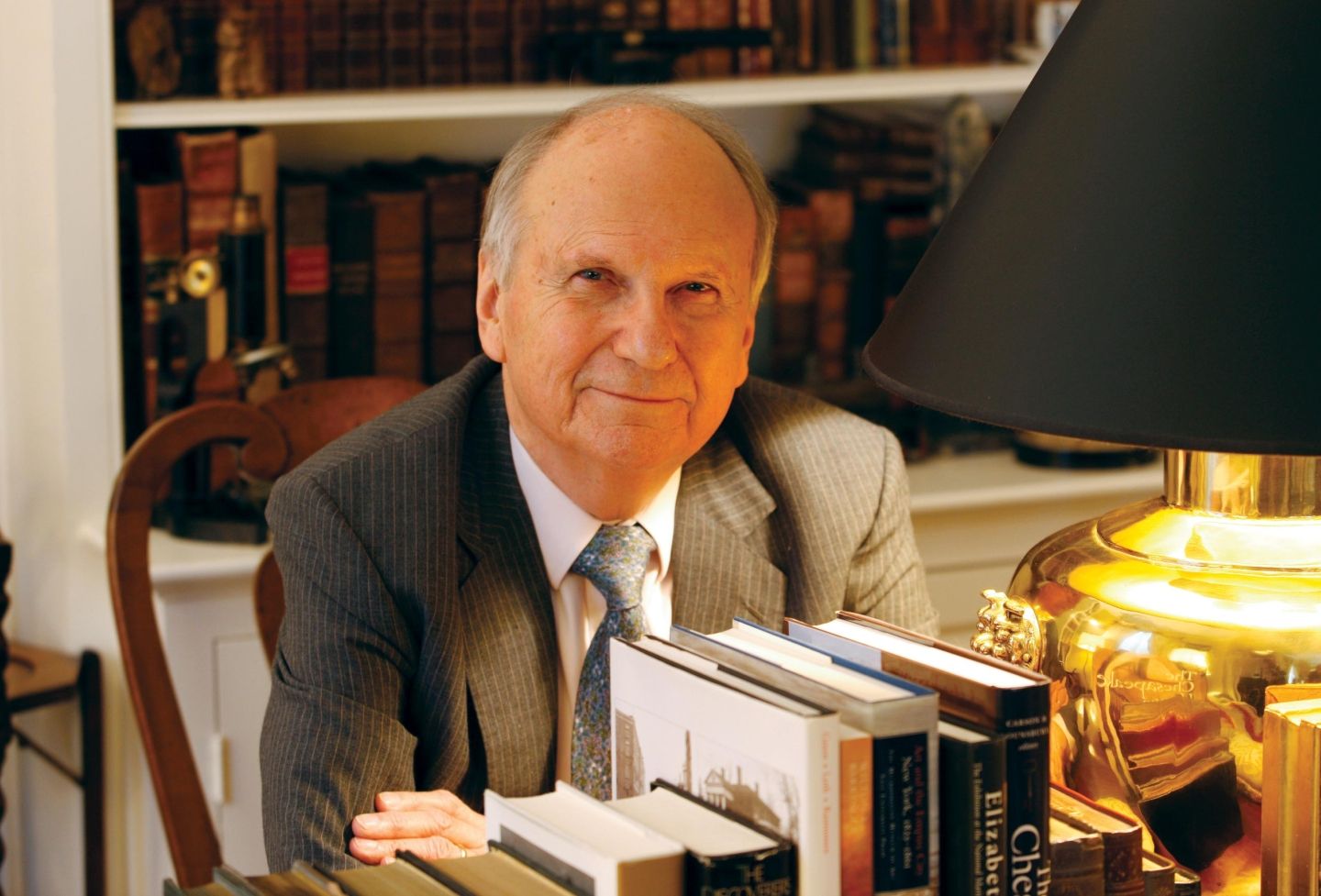

“Our success rate is probably as good as any law firm that has tried to get a Supreme Court case,” said Professor Dan Ortiz, who launched and directs the clinic. He has argued four cases before the court.

This year, Ortiz is teaching the clinic with Professor Toby Heytens '00, a former attorney for the Office of the Solicitor General who has argued six cases at the court; adjunct professor John Elwood, a partner at the D.C. law firm Vinson & Elkins who has argued nine cases at the court (Elwood is also a leading voice on SCOTUSblog and Twitter @johnpelwood); and Jeremy Marwell, one of Elwood’s law partners who has often practiced before the court. (Vinson & Elkins is the No. 1 ranked nongovernmental actor in the Villanova study — thanks, in substantial part, to cases the firm has undertaken with the clinic.)

Ortiz conceived of the clinic after seeing the model work at Stanford Law School. That class is led by Stanford law professor Pamela Karlan, Ortiz’s friend and former classmate at Yale. Karlan is also a former UVA Law professor. When Ortiz asked permission to adapt the model for Virginia, Karlan gave her blessing.

Since then, the clinic’s influence has had a ripple effect not only on Supreme Court jurisprudence, but on the careers of alumni who participated. Thirteen clinic alums have gone on to clerk at the Supreme Court, in addition to 73 at circuit courts, 41 at district courts and four at state courts.

The clinic has built its niche on identifying important conflicts in legal interpretation — often at the intersection of criminal and constitutional law — in which most law firms and movement lawyers wouldn’t first stake a claim.

The clinic introduces third-year students to all aspects of Supreme Court practice, short of actually arguing the cases in court (although they do moot their professors).

But in the beginning, the clinic was limited to two students and one cert petition — essentially a trial run during the spring of 2006. Ortiz taught the original class with David Goldberg, a lecturer with experience at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund who now teaches at Stanford.

“We loved it,” Ortiz said of the experiment. “Turns out the students did too.”

The clinic officially launched the following fall, adding a semester and another instructor: Mark Stancil ‘99, who still teaches the clinic on a recurring basis. To date, the D.C. appellate litigator and partner at Robbins, Russell, Englert, Orseck, Untereiner & Sauber has argued five cases before the Supreme Court.

The clinic's first win, in Watson, held that trading drugs for a gun did not amount to “using” a firearm in a drug transaction, for which the clinic’s client received an additional five years of imprisonment.

Madden not only found the petition, he "saw it through from the cert petition to the merits briefing,” Stancil said. Madden is now a partner in Stancil’s law firm, and the first clinic alum to argue a case before the Supreme Court — last term's successful Harris v. Viegelahn.

Since Watson, the clinic has developed multiple models for how to approach cases, and has handled issues as diverse as the appropriate venue to resolve a dispute against a credit card company (in Vaden v. Discover Bank, “a real law geek’s case,” Ortiz said) to how to interpret perceived threats made via social media (in Anthony D. Elonis v. United States, the high-profile Facebook case).

In the latter, the court left unanswered a key question: What level of intent to follow through is required when a threat is made in a public forum? Ortiz believes that dilemma, and the clinic’s work pondering related issues, will give courts something to chew on for years to come.

Last year, CBS News featured the clinic at work on its most recent case, Henderson v. United States, which focused on a felon’s right to transfer firearms he legally owns but may no longer legally possess to a third party.

The clinic won Henderson unanimously, and has bested the federal government five out of six times overall.

Casey T.S. Jonas, a law student in this year's clinic, said it's a joy to be involved with the clinic during its anniversary year.

"My team is working on a really fascinating arbitration case," she said. "Four different petitions for certiorari related to our case have been filed from different circuits, so it's exciting to see the issue and case develop before our eyes.

"There's simply nothing better than putting your head together with a team of other smart people and working on a problem."

Students and professors in this year’s clinic are working on an arbitration case.

A Short History of the Clinic at the Court

Elonis v. United States (2015)

HOLDING: To be convicted under the federal threat statute, a defendant must be aware that his communications would cause the recipient to fear harm.

DECISION: 7-2 win

Henderson v. United States (2015)

HOLDING A felon who upon conviction of his crime transfers possession of his firearms to the government and then transfers ownership to a third party does not constructively “possess” them in violation of the law.

DECISION: 9-0 win

Rosemond v. United States (2014)

HOLDING To aid and abet the crime of using a firearm during a drug offense, the defendant must know beforehand that one of his confederates will carry a gun.

DECISION: 7-2 win

Vance v. Ball State University (2013)

HOLDING To be considered a “supervisor” for purposes of vicarious liability under Title VII, an employee who harasses another must have the power to take tangible employment actions, like firing, against the victim.

DECISION: 5-4 loss

Borough of Duryea v. Guarnieri (2011)

HOLDING Public employees cannot sue an employer under the Petition Clause for alleged retaliation unless the underlying dispute implicates a matter of public concern.

DECISION: 8-1 win (with a partial dissent from Scalia)

Nevada Commission on Ethics v. Carrigan (2011)

HOLDING A law requiring public officials to recuse themselves from decisions on matters which the independence of judgment of a reasonable person in their situation would be materially affected by certain concerns does not violate their free speech.

DECISION: 9-0 win

Fox v. Vice (2011)

HOLDING When a plaintiff’s civil rights lawsuit involves both frivolous and non-frivolous claims, a court may grant reasonable attorney’s fees to the defendant, but only for costs that the defendant would not have incurred but for the frivolous claims.

DECISION: 9-0 partial win

Abbott v. United States (2010)

HOLDING A defendant is subject to the highest mandatory minimum specified for his conduct under the felon-in-possession statute, unless another provision of law directed to conduct proscribed by that particular statute, not by any other statute of whose violation he is convicted, imposes an even greater mandatory minimum.

DECISION: 8-0 loss

Bloate v. United States (2010)

HOLDING The time granted to preparepretrial motions is not automatically excludable under the Speedy Trial Act.

DECISION: 7-2 win

Vaden v. Discover Bank (2009)

HOLDING A federal court may “look through” a petition to compel arbitration to determine whether the underlying controversy “arises under” federal law; under the well-pleaded complaint rule, however, the court may not entertain a petition based on the contents of just a counterclaim.

DECISION: 5-4 win

Indiana v. Edwards (2008)

HOLDING The Sixth Amendment allows states to insist that defendants competent enough to stand trial but not able to conduct trial proceedings by themselves be represented by counsel.

DECISION: 7-2 loss

Watson v. United States (2007)

HOLDING Trading drugs for a gun does not amount to “using” a firearm in a drug transaction, for which an additional mandatory minimum term of imprisonment applies.

DECISION: 9-0 win

Note: Years indicate date of decision.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.