African-Americans played a greater role in shaping international law and the United Nations than most people realize, according to Ananda Burra, the new Charles W. McCurdy Fellow in Legal History at the University of Virginia School of Law and UVA's Miller Center.

Burra, a lawyer and visiting scholar from the University of Michigan who is completing his doctorate in the history of international law, said as early as the 1920s, African-Americans complained about colonialism to the League of Nations — the body that would become the U.N.

"It's a lot earlier than most people have thought of this kind of engagement," Burra said. "I think African-American activists in particular have a big and under-appreciated role in this moment."

Burra will serve as the second person ever to hold the McCurdy Fellowship, which is co-sponsored by the Corcoran Department of History. Burra will use the fellowship, which includes residency at the Law School for the 2016-17 academic year and a $32,000 stipend, to receive feedback on and complete his dissertation, "'Petitioning the Mandates': Anticolonial and Antiracist Publics in International Law." The dissertation tracks the development of public international law from the 1920s to the 1960s, focusing on the transition from the League of Nations to the United Nations. The role African-Americans played in developing jurisprudence is just one aspect.

As part of his research, Burra will study files from the League of Nations' archives in Geneva. The league, which was formed after World War I, was the first international organization to attempt to maintain world peace. Burra's source material includes documents from prominent African-Americans, including NAACP co-founder W.E.B. Du Bois and political scientist Ralph Bunche, who interacted with the league's Mandates Commission, which oversaw the administration of territories taken from the German and Ottoman empires. The league believed it had a responsibility for the welfare of these nations because it considered them not developed enough to cope with modernity. Residents of these "mandated" nations petitioned the league to redress violations of international law by the administrators put in charge of them. The goal of outside activists, such as those from the U.S., was to seize upon the petitioning process as a means of airing international and domestic human rights grievances.

"African-American international lawyers and international activists based out of Howard University were engaging with the League of Nations and the U.N. at a very early period," Burra said. "They were accessing forums for international law and international justice both on behalf of African-Americans and in the context of global anticolonial struggles. So they were using these international forums to make both domestic and international claims."

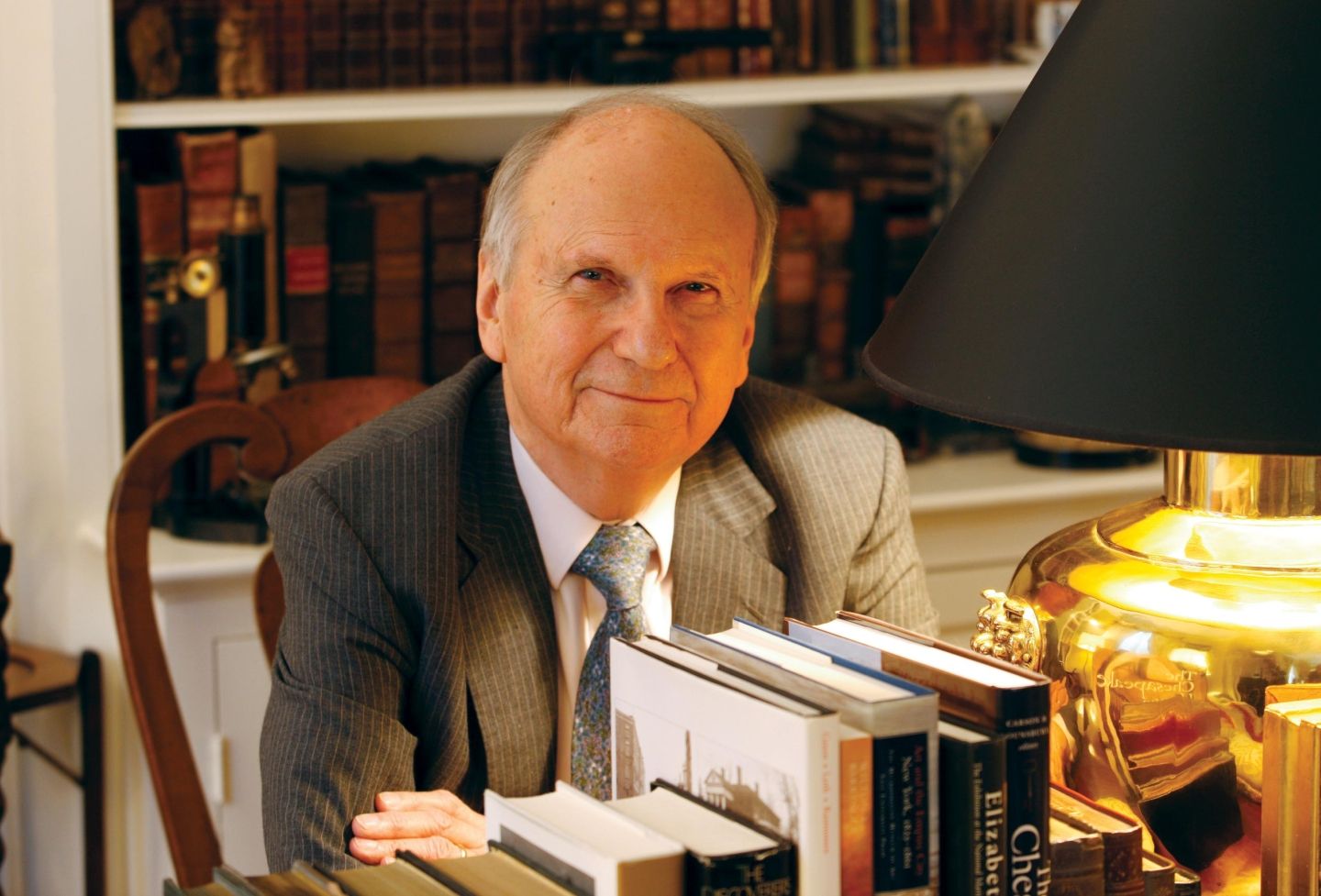

Professor G. Edward White, the Law School's senior legal historian, said the activism is an important story that is not widely known. But he said Burra's research has the potential to change that.

"Eventually, through the work of those activists and the repeated filing of petitions from residents of mandated nations, the stage was set for a 1956 decision by the International Court of Justice [the principal judicial organ of the United Nations] that the right to mount challenges to colonial administration through petition was an essential part of international law," White said. "Using hitherto unexplored archival sources in addition to the Mandates System petitions, Ananda seeks to recover important dimensions of mid-20th century anticolonial activity and international law. His dissertation has the potential for reorienting existing scholarship in both of those areas."

Burra holds both a J.D. and a master's degree in history from Michigan, and a bachelor's degree in history and international studies from Williams College in Massachusetts. At Michigan, Burra has been a contributing editor of the Michigan Law Review and authored a draft note examining how administrative regulations by international organizations can create individual rights under international law. A citizen of India, Burra clerked at the International Court of Justice and has worked in the areas of international public policy, human rights, journalism and teaching. His positions have taken him to Europe, South Asia and the Middle East, in addition to the U.S.

Burra said he hopes the dissertation contributes to the current debate on the rights of individuals within the context of international public orders and international institutions.

"The U.N. charter has an article on how individuals can petition, and there is basically no work done on where that comes from," Burra said. "My dissertation will be engaging with the question of how this form of individual access develops."

Burra's work has been presented at a number of international legal history conferences, and he holds an administrative position with the American Society for Legal History. As a responsibility of the fellowship, he will help coordinate the Legal History Workshop at UVA Law, which invites members of the History Department and other scholars to join Law School faculty for a discussion of works in progress. Burra will have the opportunity to present at the workshop as well.

“We are so excited to have Ananda as the second McCurdy Fellow," said legal historian and Law School incoming dean Professor Risa Goluboff. "Ananda is an academic superstar, and his work in the history of international law will engage many on the faculty of the Law School and the History Department, as well as at the Miller Center. He has only been in the building a week, and already colleagues have been stopping by my office to exclaim how fascinating his work is."

As one of 11 Miller Center fellows from different disciplines, Burra will benefit from the center's career guidance and high-profile reputation for bringing the lessons of history into the public discourse. He will also benefit from the relationships he forms, which will include working with a "dream mentor" not yet named. The center's program has launched the careers of numerous scholars who employ history to shed light on American life and global affairs.

As UVA welcomes Burra, it says goodbye to inaugural fellow Sarah Seo. In addition to completing her dissertation on individuals' rights as they relate to their vehicles, Seo was a contributor to the academic community who stepped up to teach Crime and Punishment In American History after an unexpected teaching vacancy, and who also published "The New Public" in the Yale Law Journal and a related co-authored op-ed in the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

“We had high hopes for Sarah as the inaugural McCurdy Fellow, and she surpassed them all," Goluboff said. "It is not just that, as the McCurdy Fellowship intends, she actually finished her dissertation during the fellowship year. Nor is it only that the dissertation is so smart, sophisticated, fascinating and beautifully written. It is also that Sarah became truly integrated into the intellectual community of the Law School. Her sparkling presence was appreciated by all, and she will be missed.”

Brian Balogh, who founded and chairs the Miller Center National Fellowship Program, said Seo will be a tough act to follow, but Burra is up to the task.

"It will not be easy to fill Sarah Seo’s shoes, but if anybody can, it is Mr. Burra," Balogh said. "He brings a global perspective and remarkable record to the McCurdy Fellowship.”

The McCurdy Fellowship is named after Charles McCurdy, a UVA professor of history and law who directed or advised more than 200 doctoral dissertations, master's theses and undergraduate theses during his 40-year career.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.