In 1949, Gregory Hayes Swanson took his first step toward integrating the University of Virginia and becoming a civil rights hero with a radical act: applying to a graduate program.

The Law School initially accepted the 25-year-old attorney’s application, but the official response by the University of Virginia Board of Visitors in July 1950 was to the contrary:

“The applicant is a colored man. The Constitution and the laws of the State of Virginia provide that white and colored shall not be taught in the same schools.”

Swanson, a Virginia native from Danville, was already practicing in Martinsville, Virginia. Having obtained his law degree from Howard University in Washington, D.C., he needed a master’s in law to be eligible for a prospective teaching job. He had no other choice but to apply to UVA if he wanted to pursue the advanced degree in his home state, where it would be less expensive to attend. No Virginia university offered graduate training to black law students.

So he sued.

Famed civil rights attorneys Thurgood Marshall, Oliver Hill, Martin A. Martin and Spottswood Robinson of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund assisted Swanson in the lawsuit, which played out in federal court in Charlottesville on Sept. 5, 1950.

His admission to UVA, were it to happen, would be “a triumph in the struggle to break down segregation and discrimination,” he said in a personal correspondence.

After a 30-minute trial and deliberation, a three-judge panel decided Gregory Hayes Swanson v. the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia in Swanson’s favor.

Read More

- Saying ‘No’ to Wall Street and ‘Yes’ to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund: Elaine Jones ’70

- Black Law Students Mattered: BALSA's Impact

- ‘I Represent All the Students and This Is What I Want’: Linda Howard ’73

- One Student’s Debt: Alfonso Carney Jr. ’74

- Erasing the Color Line: Ted Small ’92 Looks Back on SUPRA

- The Great Indoors: REI General Counsel Wilma Wallace ’89

- The Jacksons’ Judicial Philosophy: Raymond ’73 and Gwendolyn Jackson ’72

- Generation Next: The Phipps Family

- Standard-bearers: Outstanding Black Alumni

He registered for his law classes 10 days after the decision, in time for the start of the school year.

Accepted, and Seeking Acceptance

What was life like for UVA’s first black student?

Swanson rented a room at the Carver Inn, which was located in Vinegar Hill, a historically black part of Charlottesville. He walked about a mile each way to classes. He once wrote to his sister Marguerite describing how, as he traveled, he would be stared at by whites who no doubt realized him to be the first black student.

“I should like to read their minds,” he stated in the letter.

“Sometimes I think that I do."

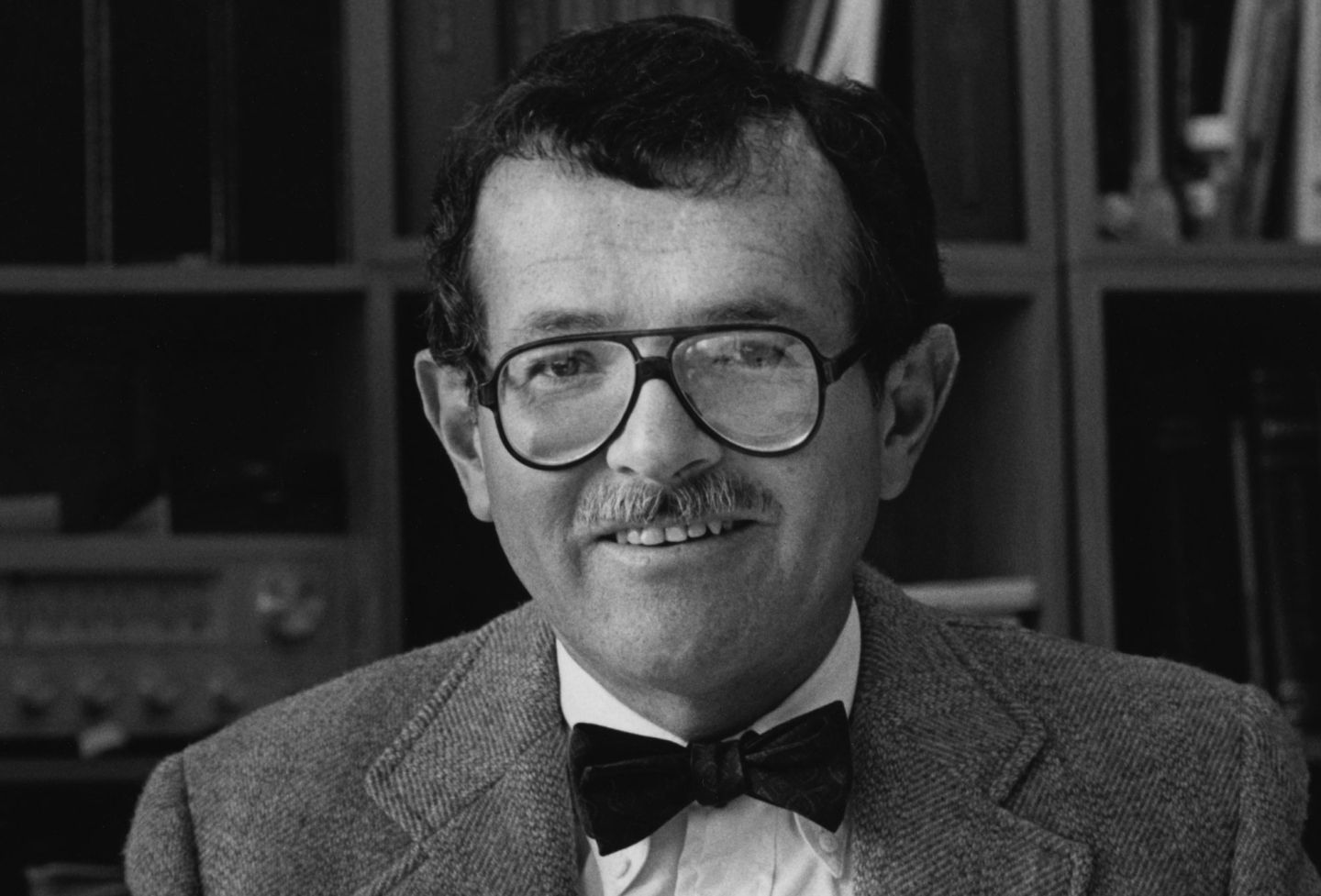

Gregory Hayes Swanson became the first black student at UVA Law in 1950. Courtesy the Swanson Family

While on Grounds, Swanson made a concerted effort to engage with others in his new environment.

“I am endeavoring to participate [in] the University activities as much as possible so that the students can get used to the idea of a Negro being here,” he wrote to Marguerite in September 1950.

Swanson was not segregated in the classroom or at the events he attended. Professor Leslie Buckler, the director of the graduate program, had Swanson to his home for meetings, just as the adviser did with white students. Law Librarian Frances Farmer hosted a faculty tea in Swanson’s honor.

Among the students, he developed several close friends.

Not all of his peers were welcoming, though. Swanson once overheard a casual conversation between students in which one said, “We should get that n---er out of the law school.”

Referencing the UVA Honor System, Swanson addressed the incident in a personal correspondence: “To pledge not to steal, lie, cheat, etc. and yet be permitted under the same pledge to say humiliating things about another student puts the Honor System in question.”

Years later, in a Sept. 1, 1958, Washington Post interview about his experiences, Swanson would state he “fully participated in classroom discussions and used all campus facilities — cafeterias, libraries. I just picked my classroom seat at random as everyone else did. I attended concerts, lectures and football games but never attempted to attend any social events.”

Swanson, while at Howard, had been deeply involved in Alpha Phi Alpha, the oldest black fraternity. He complained about his exclusion from UVA fraternities to President Colgate Darden, who stayed in routine communication with Swanson during his studies. Darden responded that fraternities were outside of the University’s oversight, but that he considered them overrated.

Swanson said in the Post article that he had known “there might be reactions, no matter how covert, to my admission, but I felt I was adequately prepared to meet them. There was no incident, however. I was well received and courteously treated.”

But in an Oct. 5, 1950, letter to one of his Howard friends, Swanson revealed that he also felt uneasy.

“I have not been able to detect any perceptible indications of hostility or bias; it is one of those things in the under-current. You can’t put your finger on it, but you know that it is there.”

Gradualism on Grounds

When Swanson applied to UVA, graduate-level desegregation was on the horizon.

The 1948 Supreme Court case Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma established that states had to provide black college students with access to schools of equal quality, or admit them to schools designated for whites. After the decision, plaintiff Ada Sipuel, a black prospective graduate law student, was admitted to Oklahoma’s law school because the state did not already have such a program available for African-Americans.

Since Virginia had the state’s only graduate legal program, Darden and Law Dean F.D.G Ribble ’21 began planning for a qualified applicant like Swanson shortly after Sipuel, according to Professor J. Gordon Hylton ’77, an expert on the Law School’s history.

Two other cases involving race in graduate education, Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Board of Regents, were pending at the Supreme Court when Swanson’s application came to the attention of University leadership.

UVA waited for decisions in those cases — both of which were decided in June 1950 in favor of the African-American plaintiffs.

Despite these decisions, the University took the public position that it could not admit Swanson because of his race and denied his application.

In the midst of a financial crisis, school officials feared that integrating proactively would lead to a backlash from lawmakers who held the purse strings, and that white students might enroll elsewhere. So the University would only admit Swanson through a court order, Hylton said.

The University’s lawyers, Charles Venable “Ven” Minor ’25 and Virginia Attorney General J. Lindsay Almond Jr. ’23, maintained the position as the case progressed that the court ruling be limited to graduate students. Spottswood Robinson, Swanson’s principal lawyer, originally pushed for the entire University to be integrated, Hylton said.

Though that didn’t happen, Swanson was still the first student known to break the color line at a college in a former Confederate state.

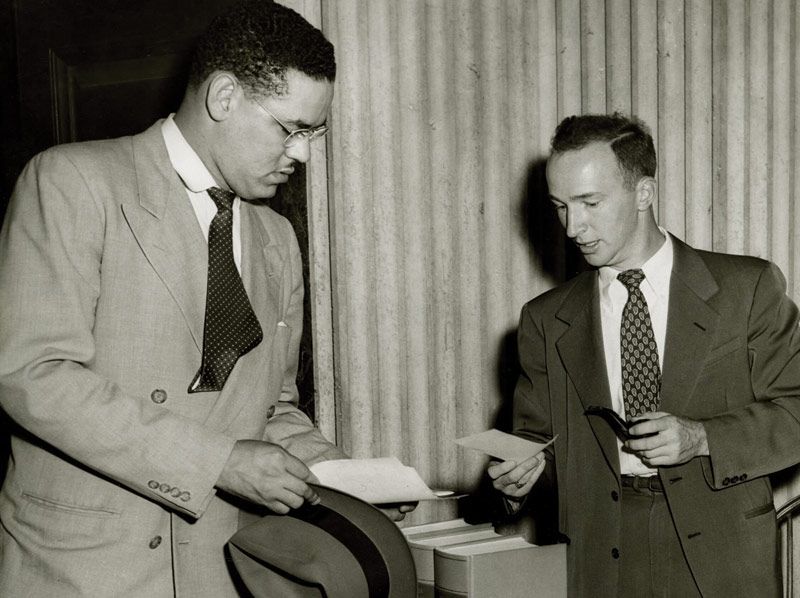

<p>Swanson consults with Assistant Law Dean Charles Woltz after registration at UVA on Sept. 15, 1950. <em>Photo courtesy UVA Law Library</em></p>

Life After UVA Law School

Like many of his law graduate peers during the period, Swanson never turned in the paper that would have allowed his degree to be conferred.

The program required one year in residence and then completion of a thesis, the latter of which usually occurred after the student had left Grounds. That was the path Swanson followed: completing and passing the eight classes he chose to take during the year — despite not being required to take any — and working on the paper after his time at UVA.

While Swanson’s communications with Buckler indicated he had every intention of completing his draft paper, the Robert H. Terrell Law School in D.C., where Swanson wanted to teach, closed in 1950. This would have eliminated his immediate need for the degree.

Plus, there were the demands of practice.

One case no doubt consumed much of Swanson’s time as he transitioned from law school life. In June 1951, he took up the defense of Albert Jackson, a black man accused of raping a white woman in Charlottesville. Swanson argued that Jackson’s confession had been obtained under duress. Following the man’s conviction, at which the court sentenced him to death, Swanson appealed to the Supreme Court of Virginia along with the counsel of Hill, Martin, and Robinson.

The appeal was unsuccessful, and Jackson was put to death in August 1952.

The Virginia Law Weekly interviewed Swanson in 1951 about the case. The article reported that Swanson “feels an advocate for his race and has a deep sense of responsibility wherever his services are needed, whether in the courtroom or in the community.”

After private practice in Martinsville and Alexandria, Swanson entered public service in 1961 as an attorney for the Internal Revenue Service. Commissioner Mortimer Caplin ’40, Swanson’s professor at UVA during his first year on the faculty, hired Swanson after Robert F. Kennedy ’51 helped renew their connection.

Swanson worked for the IRS until his retirement in 1984.

He died July 26, 1992, at his home in Kensington, Maryland.

Swanson’s official portrait is now on permanent display at the entrance of the Law School’s Arthur J. Morris Law Library. The location, fitting for a man remembered as an avid reader, is perhaps the most traveled spot in the building.

Special thanks in the research of this article to Randi Flaherty (M.A. ’08, Ph.D. ’14), J. Gordon Hylton ’77 and the archival departments of the Law School and Howard University.