They are a rarity for UVA Law: judges who are husband and wife.

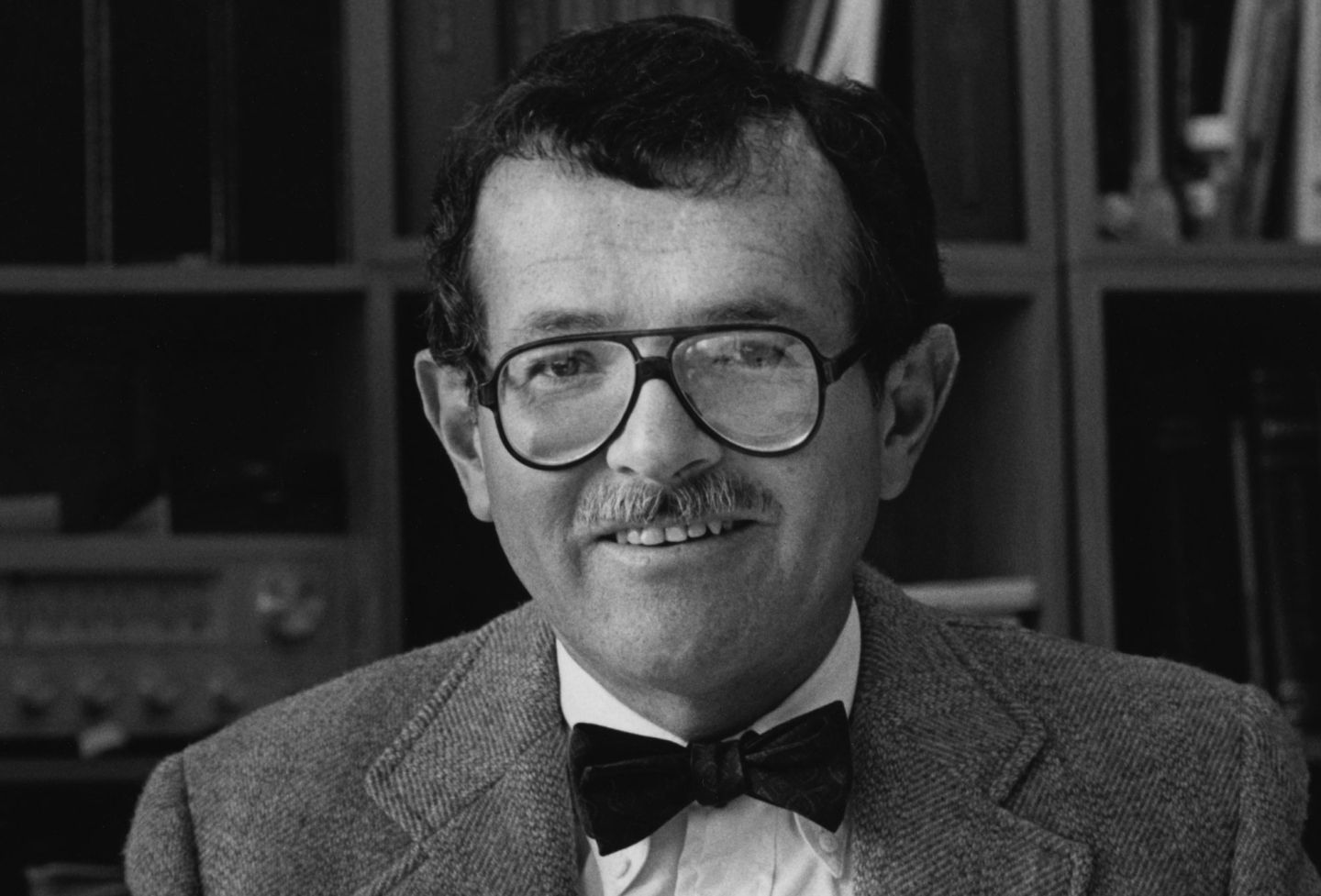

Judge Raymond Jackson ’73 sits on the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. Appointed by President Bill Clinton in 1993, he was the first African-American federal judge to serve in South Hampton Roads.

Judge Gwendolyn Jones Jackson ’72 is retired from the Norfolk General District Court, but still hears cases as a substitute judge. When appointed by the Virginia General Assembly in 1991, she was the first African-American female judge in South Hampton Roads, and only the second woman appointed to Norfolk General District Court bench.

The Jacksons, during their pioneering careers, have heard cases on almost every topic that can be brought to court.

With each one, they said, they have endeavored to bring a professionalism to the bench that reinforces the dignity of all participants, while keeping the best interests of their community in mind.

Considering Others’ Time

Judge Raymond Jackson said a judge first demonstrates respect by being prepared.

“The Eastern District of Virginia has a reputation for being very quick and efficient in disposing of litigation,” he said. “It is often called the ‘rocket docket.’ As a judge, I try to make sure I am prepared when I walk into the courtroom, and that I do not waste the litigants’ time in addressing issues.”

His caseload is a mix of high-stakes civil and criminal cases, driven in part by the large number of federal employers in the district and the litigation they inevitably generate.

He may hear a homicide case one day, a patent infringement case the next.

The judge is also well-known on the bench for being an outspoken proponent of sentencing reform whose interpretation of federal sentencing guidelines in Kimbrough v. United States was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2007. The decision affirmed judicial discretion in sentencing the possession, distribution and manufacture of crack cocaine — which carried heavier prison time compared to similar powder cocaine offenses.

Jackson played Handel’s “Hallelujah” chorus on a boom box in his office when he received the news of the Supreme Court’s ruling.

Members of the Black American Law Students Association in 1972 included: (front row) Bryant Mitchell '75, Raymond Jackson '73, Leroy W. Bannister '73, Barbara Liles '74 (back row) John W. Scott Jr. '73, Arthur McFarland. Photo courtesy UVA Law Library/Virginia Law Weekly

Just as he remembers every person he sentenced to death, he remembers every person he sentenced to life in prison once mandatory minimums took effect.

“After 24 years, their families are still writing,” he said. “I do not have any remedy for them, though I realize [the family member] should never have received a life sentence.”

Jackson said his early-career exposure to federal litigation, in addition to a host of civic and community involvements, led to his appointment to the bench.

He started out as an officer in the Judge Advocate General’s Corps of the U.S. Army, gaining extensive experience trying courts-martial as chief defense counsel at Fort Bragg and the Training and Doctrine Command at Fort Monroe. (He would later retire from the U.S. Army Reserve as a full colonel.)

He subsequently joined the U.S. attorney’s office in Norfolk, where he rose to executive assistant U.S. attorney and was the first African-American to manage the offices in the Norfolk and Newport News divisions of the court. He also served as chief of both the civil and criminal divisions.

Over his career, Jackson has been involved in numerous professional organizations. He has served extensively in leadership roles with the Virginia State Bar, including chairman of the Standing Committee on Lawyer Discipline and Bar Council representative, and is a past president of the Old Dominion Bar Association. From 2000-02, he served as president of the Anson-Hoffman Chapter of the American Inns of Court.

He has taught as an adjunct professor at William & Mary School of Law, and at bar associations and judicial conferences. He earned his bachelor’s in political science from Norfolk State University.

In addition to being an instructor and mentor to new federal judges, Jackson has provided opportunities to students as clerks and externs, and spoken at schools and other venues to encourage those aspiring to the legal profession, perhaps even to the bench.

Read More

- The Long Walk: How Gregory Swanson Integrated UVA and UVA Law

- Saying ‘No’ to Wall Street and ‘Yes’ to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund: Elaine Jones ’70

- Black Law Students Mattered: BALSA's Impact

- ‘I Represent All the Students and This Is What I Want’: Linda Howard ’73

- One Student’s Debt: Alfonso Carney Jr. ’74

- Erasing the Color Line: Ted Small ’92 Looks Back on SUPRA

- The Great Indoors: REI General Counsel Wilma Wallace ’89

- Generation Next: The Phipps Family

- Standard-bearers: Outstanding Black Alumni

“There’s a dearth, still, of African-American lawyers,” he said. “I think it’s always important to give back, to reach back, and extend a hand to bring someone else along.”

Hearing Others’ Voices

Judge Gwendolyn Jackson estimates she heard about a million cases — literally — before giving up full-time status on the bench in 2015 after 24 years.

While the matters may be deemed less serious by statute than those in federal court, they are no less important to the people who come seeking justice, she said.

Jones received the Constance Baker Motley Scholarship Award of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund in 1972 from Professor Emerson Spies and Dean Monrad G. Paulsen. Photo by Bill Hinkle/UVA Law Library/Virginia Law Weekly

“People being put out of their homes, forced into the street; contract cases where house repairs have caused serious, destructive damage; automobile accident cases where someone is seriously injured,” she said as examples of the types of cases her court hears. “All of the cases are important to the litigants.”

The judge said her ability to actively listen to participants’ concerns has been essential.

“The majority of people have their first legal experience in general district court,” she said. “I believe you should listen to the people. They will be willing to accept even an adverse court ruling if they know they’ve been heard.”

Jackson served a four-year stint as chief judge, having been voted to the position twice by her peers. During that period, she helped implement a segmented docket by meeting with representatives of the Norfolk Police Department, Virginia State Police administrators and the Office of the Executive Secretary of the Virginia Supreme Court, in order to set times when specific types of cases would be heard in the district court. These specific assignments helped to prevent litigants from regularly being summoned to court at 9 a.m., only to not have their cases heard until 2 p.m. or later.

The change ultimately meant the public could have their day in court without spending their whole day there.

Before being appointed to the bench by the Virginia General Assembly, Jackson was an attorney for 18 years in several capacities, culminating with her becoming the only female partner in the Norfolk law firm Sams, Shelton, Anderson and Jackson. She represented clients in cases involving employment and business law, personal injury litigation, real estate and other concerns.

She began her career with the civil rights law firm Hill, Tucker & Marsh, in Richmond, Virginia, handling employment discrimination cases and other matters of general practice.

“One day, one of the partners said to me, ‘Gwen, you should go to state court and learn how to try a traffic case.’ So I went to the Richmond Traffic Court and tried that traffic case. Who would have thought that 18 years later that my first assignment as a judge would be in traffic court?”

Like her husband, Jackson has had a career-long commitment to community service. She served for a decade on the Vocational Education Advisory Council of the Norfolk School Board. She served three terms on the board of the City of Norfolk Employee’s Retirement System, which managed a $300 million retirement fund, and was chair for a period. She served as the first Area II director of the Hampton Roads NAACP. In 1987, she received the NAACP Legal Defense Fund Pro Bono Award.

Jackson also has taught a young adult Sunday school class for more than 20 years, and encouraged young people in and out of court to read and participate in their community.

She earned her undergraduate degree in English from Hampton University, and is a member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, The Silhouettes of the Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity Inc. and The Woman’s Club of Norfolk.

Bringing Work Home

Given that judges are known to have the final say, has living in a two-judge household ever been — trying?

Not at all, they said. Their differing venues, and, by default, dissimilar cases, have made it easy to avoid philosophical disputes. Besides, at home, family comes first.

“We have always basically had our focus on raising our children and being involved in their daily activities,” Raymond Jackson said.

“While the children were growing up, we planned family dinner every night,” Gwendolyn Jackson said. “We did not discuss legal cases, but current events and life challenges.”

Though work wasn’t discussed, over the years they brought home a lot of it. So much so that their three children said they would never be lawyers.

The respect their parents exhibited for the legal process must have worn off, however. Two of their now-adult children are attorneys, while one is a member of the clergy.

The Recruiting Visit

Gwendolyn Jones was an English major in her fourth year at Hampton University, certain she would go on to earn her Ph.D. in English and become a teacher, when her sister, Elaine Jones, a student at UVA Law, paid a visit.

Elaine Jones was on a recruiting trip with a law school administrator. They were in search of black undergraduate students who were interested in becoming lawyers. Gwendolyn Jones had agreed to help assemble fellow Hamptonians.

But what the younger sister said at the end of the day came as a shock to both siblings.

“I was standing there after they had finished interviewing the other students, and I said, ‘You should interview me.’”

“Interview you?” the older sister said, incredulous.

They’d never discussed a mutual interest in the law before. But as it turned out, her sister had been more of a role model than she realized.

“I think the fact that my sister was the first African-American female admitted to the Law School was a factor,” said Gwendolyn Jones, now Gwendolyn Jackson, who began law classes in 1969.

A year later, Raymond Jackson began his education at the Law School.

“I never had a great plan to come to the University of Virginia Law School, because I had been admitted to other law schools,” he said. But a friend — who turned out to be a former classmate of his future wife — “persuaded me of the great value in coming.”

“It was a wise choice,” Gwendolyn Jackson affirmed.