An Obama-era consumer policy meant to help investors could end up costing them, says University of Virginia School of Law professor Quinn Curtis.

In his new paper, “Regulating Investment Advice: Lessons from the DOL Fiduciary Rule,” Curtis explains the possible unintended consequences of the Fiduciary Rule, an Obama administration policy that was designed to help consumers.

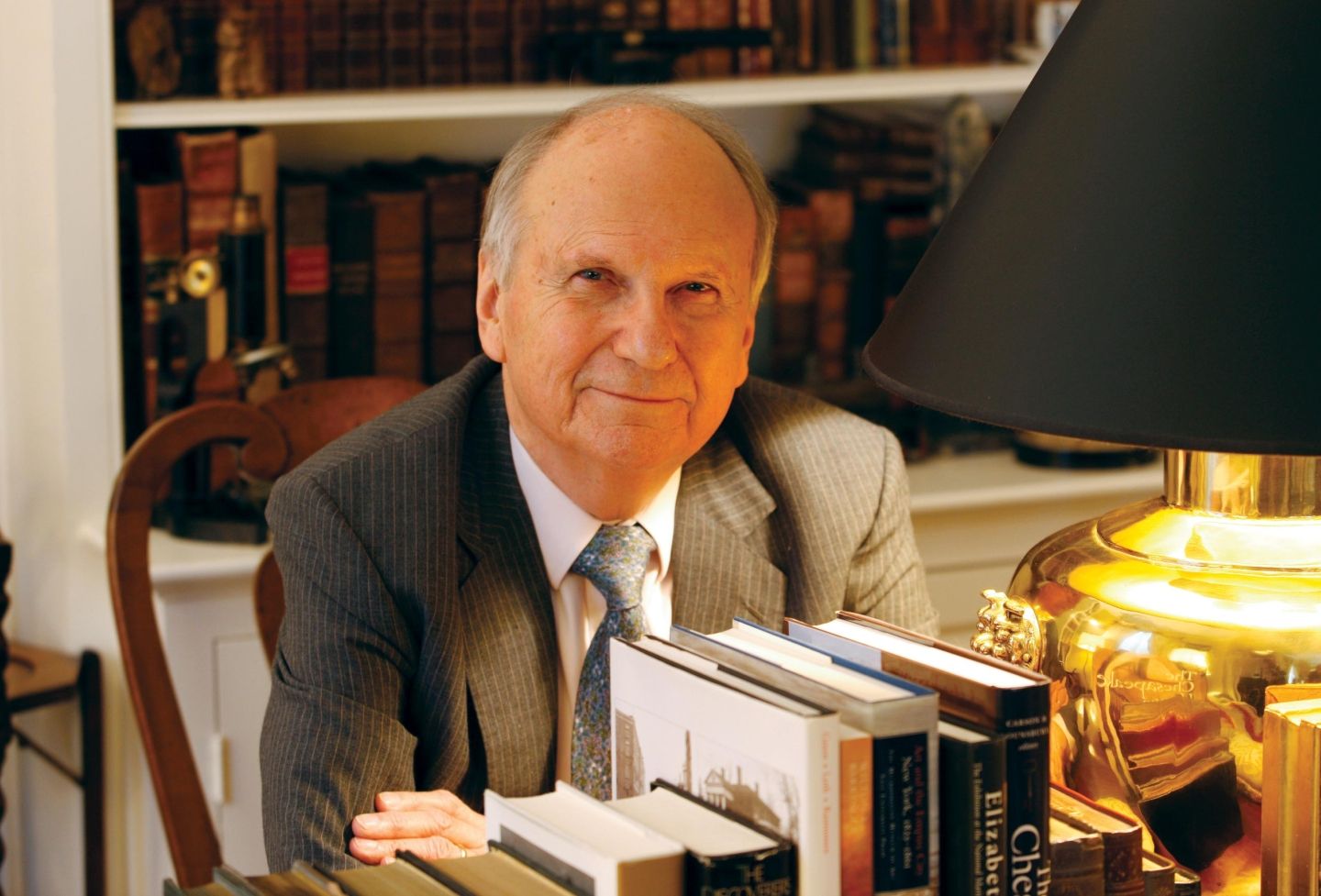

Curtis, the Albert Clark Tate, Jr., Professor of Law, has written extensively on the regulation of mutual funds and retirement accounts, including empirical work on 401(k) plans, mutual fund governance and fee litigation.

He recently answered questions about the rule’s impact on the financial services industry and what can be done to benefit stakeholders.

So what is the Fiduciary Rule?

The Fiduciary Rule is an initiative from the Obama administration Department of Labor to reduce conflicts of interest in investment advice. The Fiduciary Rule has a lot of complicated consequences, but at its heart it expands the number of brokers and other financial professionals who are required to act in their clients’ best interest and avoid conflicts of interest when giving advice with respect to their clients’ retirement accounts. This affects people who are rolling over a 401(k) or investing in an IRA. The rule is designed to ensure that the advice they get is unconflicted.

What’s the status of the rule?

Right now, the rule is on an 18-month hold while the Donald Trump administration reviews and, presumably, revises it. Meanwhile, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission is preparing its own version of the Fiduciary Rule, so there’s likely to be a lot of action in this area over the next couple of years.

Why wouldn’t a broker act in the best interest of a client?

Brokers are commonly compensated through mutual fund “loads.” These are sales commissions, often as much as 5 percent of the invested amount, that are paid directly to the broker. Not all mutual funds carry commissions, and some mutual funds carry commissions that are higher than others. Brokers have incentives to recommend these funds. Legally, without a requirement to act in the best interest of their clients, brokers only need to show that the funds are “suitable” and not that they were the best options. A lot of academic evidence suggests that funds that carry loads are poor performers relative to other funds.

How does the Fiduciary Rule address this issue?

By making brokers fiduciaries, the rule sharply limits their ability to receive sales loads. Fiduciaries are not permitted to have conflicts of interest. Under the rule, brokers can receive sales commissions only if steps are taken to ensure that the brokers’ recommendation is not distorted by the commission — by making sure commissions across all mutual funds are the same, for example — and if the broker enters into a contract with the client promising to act in their best interest.

Is this likely to leave investors better off?

I think it’s pretty unclear, and that’s what the paper’s about. Brokers’ commissions pay for advice. It’s true that advice is conflicted, and the evidence suggests that investors could do better if they got unconflicted advice. But the rub is that unconflicted advice is expensive, too — often about 1 percent of assets per year. The question is, are you better off getting cheap conflicted advice or expensive unconflicted advice? In the paper, I do some simple calculations and find that it’s a pretty close call.

What’s clear, though, is that if investors could get commission-based advice without conflicts of interest, then that would be a good outcome, but it’s not clear that the Fiduciary Rule will make that happen.

What are some specific areas of concern with the rule?

There are two issues with the Fiduciary Rule as it relates to commission compensation. First, even if a brokerage features funds that all have the same sales load, they are still load funds, and the academic literature tells us that those kinds of funds are likely to underperform. Even though the conflict of interest is mitigated to some degree by leveling out the loads, what we really need is to ensure that the whole universe of mutual funds is available to broker-advised clients, and the Fiduciary Rule can’t do that.

Second, the requirement that the broker enter into a contract with the client means that the client has grounds to file a lawsuit if any of the fiduciary duties are breached. On its own, this may or may not be a bad thing, but the contract requirement applies only to commission compensation and not when the adviser charges an annual percentage of assets. Given all the uncertainty about the new fiduciary duty, the worry is that this liability will scare brokers away from using commission compensation. The problem is that advisers that charge an annual percentage tend to charge more. Given the other requirements of the rule, it’s not clear how much value private lawsuits add, but they pose a real risk of pushing investors to more expensive compensation models.

What can be done to improve the rule?

The rule could be tweaked to limit liability under the contract, and — in principle — the SEC could change the rules around sales commissions to allow brokers to sell funds that currently can’t be sold with a load. Both of these changes could make the rule more effective at achieving its goal of helping investors.

But the root problem is that full-service investment advice is expensive. For a lot of investors with typical needs, we should be looking for policies that reduce the need for advice in the first place because that’s where the real savings are. The Department of Labor has a lot of authority over the structure of 401(k) plans and could use that authority to encourage plan sponsors to provide comprehensive default and even rollover options. Employers could also be encouraged to offer more comprehensive planning through their 401(k) programs. If most assets can be kept in the 401(k) system, and we can leverage that system to provide good options when an employee retires, investors could save a lot of money and have better access to unconflicted advice.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.